High perioperative lactate levels and decreased lactate clearance are associated with increased incidence of posthepatectomy liver failure

Mihi Popesu , , Simon Dim , , Vldislv Brsovenu , Andrd Tudor ,Mihi Simionesu , Dn Tomesu ,

a “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest 020021, Romania

b Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest 022328, Romania

c “Dan Setlacec” Center for General Surgery and Liver Transplantation, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest 022328, Romania

TotheEditor:

Extensive liver resection represents a life-saving intervention in patients with primary or secondary liver tumors. Recent advances made in the field of chemotherapy and surgical techniques have translated into a greater number of patients who are older and with more complex comorbidities presenting for major liver surgery [1] and thus having an increased risk of perioperative mortality. Of those, posthepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) represents a life-threatening complication of liver surgery and one of the most important causes of perioperative mortality. The incidence reported in current literature varies between 4.9% and 32% [ 2 , 3 ].Such patients need to be managed by a multidisciplinary team in a dedicated intensive care unit to minimize multi-organ dysfunction associated with PHLF [4] . We hypothesized that lactate dynamics in the setting of liver surgery can be used as a marker of poor liver function. This study aimed to assess the correlation between lactate levels, lactate kinetics and postoperative PHLF in the perioperative period of major hepatic surgery.

We prospectively included patients who underwent major hepatic resection for primary or secondary liver tumors in a single university hospital over a period of 12 months (between March 2017 and March 2018). Exclusion criteria consisted of age under 18 years, death within 24 h after surgery, perioperative need of renal replacement therapy, patients with underlying liver cirrhosis and those who have other causes of increased lactate levels(e.g. shock). PHLF was defined in accordance with the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS) consensus definition [3] . The following data were collected before surgery: age, sex and preoperative lactate levels (T0). During surgery the following parameters were collected: lactate levels before the dissection phase (T1),lactate levels at the end of the dissection phase (T2) and end of surgery (T3), extent of liver resection, blood loss and packed red blood cells transfusion, cumulative duration of Pringle maneuver,and duration of surgery. During the postoperative period the following data were collected: lactate levels at 24 h (T24) and 48 h(T48) after surgery and clinical and paraclinical variables required for the diagnosis of PHLF. The ethical approval for the present study was provided by the Ethics Committee of Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania (No. 1223/2016).

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc?,Chicago, IL, USA). Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median (range) otherwise percentage. Data distribution was examined in order to insure the proper statistical examination. Categorical variables were analyzed with Chi-square test and quantitative data were analyzed with independent samplest-test or Mann-WhitneyUtest, as appropriate. AllPvalues were twotailed and aPvalue of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Fifty-five patients were included in the study. The mean age was 57 ± 13 years. Of the 55 patients, 29 (52.7%) underwent a liver resection<30% of liver mass, 9 (16.4%) between 30% -50%and 17 (30.9%) more than 50% of the liver mass. The mean preoperative hemoglobin and hematocrit levels were 13.0 ± 1.7 g/dL and 35.3% ± 5.8%, respectively. The mean duration of surgery was 289 ± 145 minutes and the mean duration of the dissection phase was 155 ± 92 minutes. Nine patients required Pringle maneuver during surgery for a median duration of 25 (5-60) minutes. The median blood loss was 650 (10 0-50 0 0) mL and 13 patients required a median packed red blood cells transfusion of 0 (0-3) U.

Lactate levels increased from 1.5 ± 0.6 mmol/L at the beginning of surgery to 2.0 ± 1.3 mmol/L before the dissection phase and to 2.2 ± 1.0 mmol/L at the end of the dissection phase and slightly decreased to 2.1 ± 0.9 mmol/L at the end of surgery. The mean lactate levels in the postoperative period were 2.7 ± 1.6 mmol/L at 24 h after surgery and 1.9 ± 0.9 mmol/L at 48 h after surgery.Twelve patients (21.8%) developed PHLF in the postoperative period. The 30-day mortality was 5.5% (n= 3) and all had been diagnosed with PHLF.

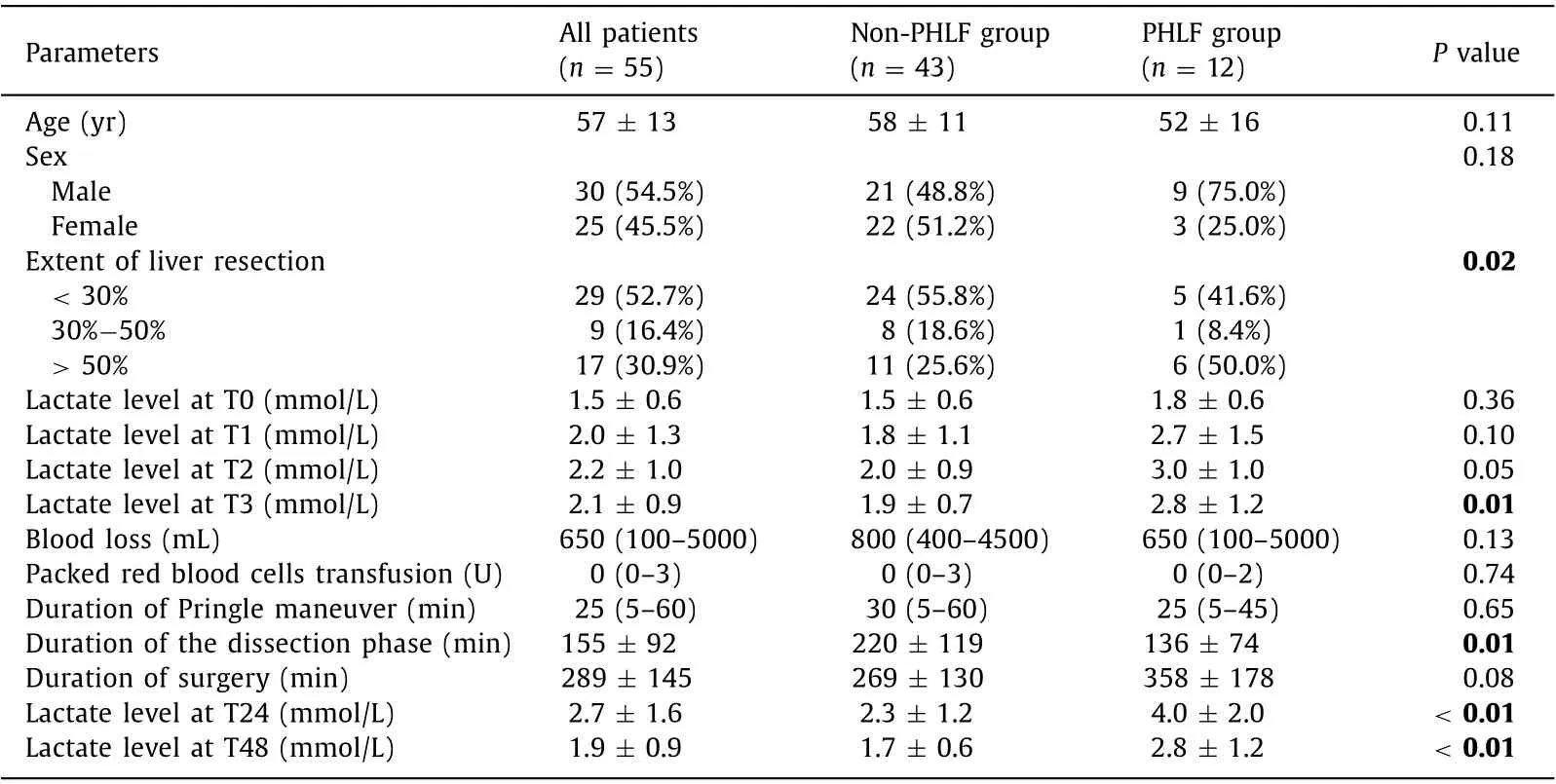

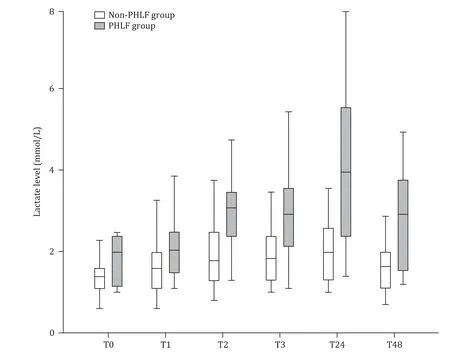

Univariate analyses identified extent of liver resection, duration of the dissection phase, lactate levels at end of surgery and in the postoperative period at 24 and 48 h intervals as independent risk factors for PHLF ( Table 1 ). Patients with PHLF had a higher increase in lactate levels than that in the non-PHLF group at the end of the dissection phase compared with the predissec-tion phase (P= 0.02), and 24 h after surgery compared with the end of surgery (P<0.01) ( Fig. 1 ).

Table 1 Perioperative factors associated with posthepatectomy liver failure.

Fig. 1. Comparison of lactate kinetics during the perioperative period.

Our results confirm a correlation between lactate levels in the intraoperative and early postoperative period with the development of PHLF. Lactate levels peaked at the end of the dissection phase in both groups but a significantly higher levels was recorded in the PHLF group. In the non-PHLF group, lactate levels returned to normal values within 24 h of surgery, while in the PHLF group they remained high during the first 48 h postoperatively. We did not find a correlation between preoperative lactate levels and postoperative PHLF as in the study by Riediger et al. [5] . This is either due to the non-urgent surgical indication of patients in our study group that allowed for adequate preoperative preparation or to the exclusion from the study group of all patients with preexisting liver disease, including liver cirrhosis. Our results demonstrate that high lactate levels at the end of surgery are correlated with an unfavorable outcome. This in accordance with data published by Vibert et al. [6] who showed that arterial lactate level>3 mmol/L is an early predictor of postoperative outcome and this should be used as a tool to determine patients requiring intensive care admission. The link between high lactate levels in the early postoperative period and adverse outcomes is also in accordance with the study published by Lemke et al. [7] . Nevertheless, our proposed algorithm of multiple assessments of lactate during the perioperative period may be superior to a single determination by offering an insight into the kinetics of lactate clearance and hence timely assessment of liver dysfunction. We also observed that lactate clearance is also reduced in patients who will develop PHLF. Thus, after the initial peak at the end of the dissection phase, lactate levels remain high throughout the first 48 h postoperative. This is in contradiction with the results presented by Pagano et al. [8] who failed to show that lactate kinetics is an independent marker or predictor for initial poor liver function after extended hepatectomy. This may be due to the longer time interval used to measure lactate clearance (defined as lactate at postoperative day 5 minus lactate at ICU presentation). Thus, using smaller time intervals for lactate measurement may prove to be more beneficial in identifying patients at risk of developing liver dysfunction. Although we observed that all patient who died had PHLF, we cannot correlate this with either lactate values or lactate kinetics and a larger study is needed to assess this issue. Nevertheless, lactate levels can be used to assess patients in the perioperative period and identify those who would benefit most from intensive care measures. In patients with high lactate levels during the intraoperative period and other risk factors for PHLF, a decision should be made by the senior anesthesiologist and surgeon whether it is safe or not to continue the surgical intervention.

In our study, the relatively small number of included patients,especially the small number of patients who developed PHLF. Although a larger cohort would make statistical analysis more robust,our results trend towards a significant difference in lactate kinetics between patients who develop PHLF and those who do not. Our results need further confirmation in a larger clinical trial that should focus on the development of a prognostic score to assess the risk of developing PHLF in the early postoperative period.

In conclusion, perioperative lactate level is a good indicator of postoperative liver dysfunction after liver surgery and should be used as guidance for decision making in this group of patients. Furthermore, lactate clearance is decreased in patients who will develop PHLF. Implementation of a protocol with well-defined time points for lactate monitoring in the perioperative period may improve patient care and early identification of those who require advanced intensive care.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mihai Popescu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review &editing. Simona Dima: Investigation, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Vladislav Brasoveanu: Investigation, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Andrada Tudor: Investigation,Project administration, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Mihai Simionescu: Investigation, Project administration, Validation,Writing - review & editing. Dana Tomescu: Conceptualization,Methodology, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fundeni Clinical Institute (No. 1223/2016) and was retrospectively registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04512014). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2021年6期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2021年6期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma with sarcomatous change:Clinicopathological features and outcomes

- Successful treatment of complete traumatic transection of the suprahepatic inferior vena cava with veno-venous and cardiopulmonary bypass with hypothermic circulatory arrest ?

- Successful withdrawal of antiviral treatment in two HBV-related liver transplant recipients after hepatitis B vaccination with long-term follow-up

- An NSQIP survey of outcomes after resection of choledochal cysts in adults

- Glucagonoma syndrome with necrolytic migratory erythema as initial manifestation

- A rare type of choledochal cysts of Todani type IV-B with typical pancreaticobiliary maljunction