Impact of cardiologist intervention on guideline-directed use of statin therapy

Manouchkathe Cassagnol,Ofek Hai,Shaqeel A Sherali,Kyla D’Angelo,David Bass,Roman Zeltser,Amgad N Makaryus

Abstract

Key words:Statin use;Guideline directed statin therapy;Cardiologist;Ambulatory care;Adherence

INTRODUCTION

Statins have an important and well-established role in the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease(ASCVD).Large-scale clinical trials have shown that statins substantially reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in both primary and secondary prevention.The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association(ACC/AHA)Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce ASCVD Risk in Adults emphasizes identifying and treating individuals at the highest risk for developing ASCVD with statins[1,2].However,despite mounting evidence supporting its use,several studies have reported widespread underuse of statins in the ambulatory setting[3],in secondary prevention[4],and more frequently among women[5],older adults,Blacks,Hispanics/Latinos,and those who are under/uninsured[6].Early skepticism of the feasibility of implementing the ACC/AHA guidelines in a patient population has been documented.One report found 56%predicted prescriber adherence to those guidelines in a retrospective simulated analysis of a large academic medical practice[6].In a more recent study,one-third of patients with ASCVD and almost one-half of patients without ASCVD were not receiving guideline recommended moderate-to high-intensity statin therapy in cardiology practices after the publication of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline[1].The most recent cholesterol 2018 guidelines from ACC/AHA continue to emphasize the use of statins as a primary treatment modality for eligible patients to achieve appropriate low-density lipoprotein cholesterol(LDL-C)reduction[2].

Limited information is available regarding the appropriate implementation of the cholesterol guidelines as they pertain to evidence-based statin use.The objective of our study was to examine physician adherence to GDST in the ambulatory setting across multiple subgroups of patients and determine the impact of cardiologist intervention on GDST.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and sample

A retrospective chart review was conducted of patients who had at least one encounter at the adult Internal Medicine Clinic(IMC)and/or Cardiology Clinic(CC)at our community tertiary care teaching hospital from May 2016 to April 2017 and who had an available serum cholesterol test performed.Patients were excluded if the following biometric variables needed for calculation of ASCVD risk score were unavailable:age,sex,race,systolic blood pressure(SBP),total cholesterol(TC),LDL-C,high density lipoprotein cholesterol(HDL-C),history of diabetes mellitus(DM),smoking status,and hypertension treatment status.In addition,patients whose demographics lacked guideline directed treatment recommendations were excluded(e.g.,age <40 or >79 years).The 2 comparison groups were defined as:(1)Patients only seen by IMC;and(2)Patients seen by both IMC and CC.

Definitions

The presence of clinical ASCVD included history of acute coronary syndrome,history of myocardial infarction,stable or unstable angina,coronary or other arterial revascularization,stroke,transient ischemic attack,or peripheral artery disease.Moderate-and high-intensity statin was defined by statin dose that would lower LDLC on average by 30%-49% and ≥ 50% with daily dosing,respectively.Statin therapy utilized was categorized as appropriate or not appropriate GDST.As such,the presence of clinical ASCVD or LDL-C greater than 190 mg/dL,would indicate use of high-intensity satin(atorvastatin 40–80 mg or equivalent)[1].For primary prevention,the presence of a diagnosis of DM and/or ASCVD risk score >7.5% would indicate the use of at least a moderate-intensity statin(atorvastatin 10-20 mg or equivalent)depending on patient tolerance[1].

Data collection and assessment

Data collected included date of visit,date of lipid panel referenced,gender,age,body mass index,race/ethnicity,TC,HDL-C,SBP,hypertension and its treatment status,presence of clinically diagnosed DM,smoking status,history of ASCVD,clinically diagnosed hyperlipidemia and current statin use including type and dose/intensity.Data were entered into the ASCVD risk calculator,with 10-Year and lifetime ASCVD risk recorded.Treatment assigned by the physician at the last clinic visit was then compared to guideline recommended treatment,and labeled as appropriate or inappropriate.If a patient’s LDL-C was greater than 190 mg/dL or if they had clinical ASCVD,then they would be eligible for high-intensity statin and use of the ASCVD risk calculator was not indicated and therefore not calculated,as per guideline recommendations.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± SD or number and percent.Baseline characteristics of subgroups were compared using studentt-tests orχ2tests,as appropriate.χ2test analysis was used to analyze statistical significance between groups.Analysis of variance was used to test the statistical difference between means of continuous variables.Statistical significance was defined asP<0.05.All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0(SPSSTMInc.,Chicago,IL,United States).

RESULTS

A total of 268 patients met the inclusion criteria for this study.Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the study population,56% were female,mean age was 56 years(± 10.65,SD),22% identified as Black or African American and 56% identified as Hispanic/Latino.Approximately 14% of the cohort had clinical ASCVD as previously defined,13% were current smokers,66% were diabetic,and 63% were hypertensive.Statin use was observed in 55% of the entire cohort,with moderateintensity statins being the most commonly prescribed.

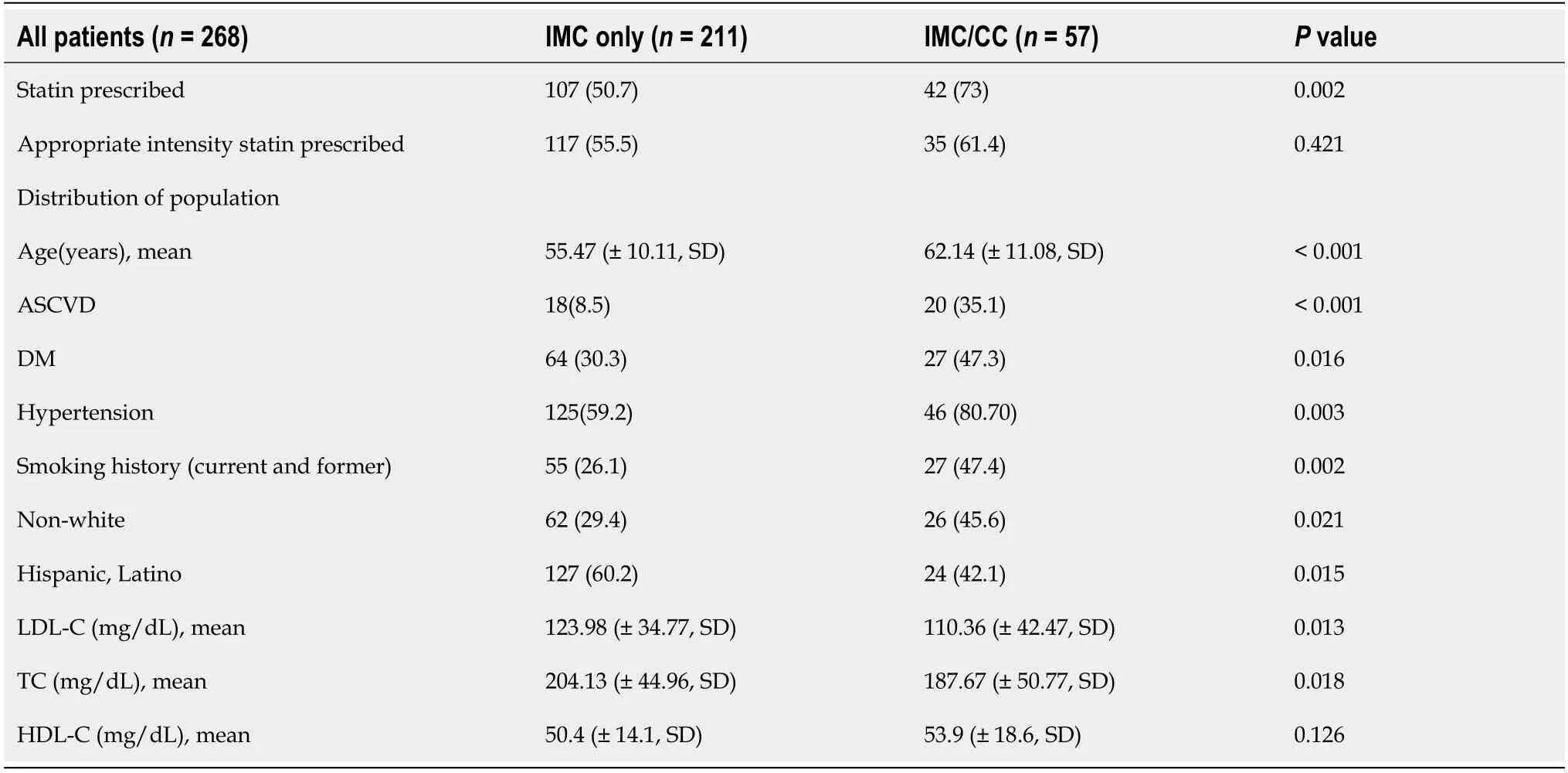

Of the total 268 patients,211 and 57 patients were in the IMC only and IMC-CC group,respectively(Table 2).Overall,in the IMC-CC group,73.6%(n= 42/57)of patients were prescribed statin therapy compared to 50.7%(n= 107/211)of patients in the IMC group(P= 0.002).In terms of appropriate statin use based on guidelines,there was no statistical difference between groups[IMC-CC group 61.4%(n= 35/57)vsIMC group,55.5%(n= 117/211),P= 0.421].Patients in the IMC-CC group had significantly higher cardiac risk as compared to the IMC group:Clinical ASCVD history(35.1%vs18%,P<0.001),diabetes(47.3%vs30.3%,P= 0.016),hypertension(80.7%vs59.2%,P= 0.003)and smoking history(47.4%vs26.1%,P= 0.002).Patients in the IMC-CC group were significantly older(mean age 62.1 yearsvs55.5 years,P<0.001)and had a higher proportion of non-white patients(49.6%vs29.4%,P= 0.021)compared to the IMC group.Mean LDL-C and TC levels were lower in the IMC-CC groupvsthe IMC group(mean LDL-C,110.36 mg/dLvs123.98 mg/dL,P= 0.013)and(TC,187.67 mg/dLvs204.13,P= 0.018).

DISCUSSION

In our evaluation of real-world cholesterol management,we found that adherence to GDST by physicians occurred in about half the patients eligible for statin therapy.The 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce ASCVD Risk in Adults(which were the latest available guidelines during our study period)recommends statins as first-line lipid lowering therapy for both primary and secondary prevention[7].Furthermore,data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys estimated an increase in statin-eligible patients by 2.4 million,2.2 million,and 8.2 million in patients with ASCVD,diabetes,and in primary prevention,respectively[8].Given recent shifts in the cholesterol treatment paradigm from the older ATP III guidelines[9],Schoenet al[6]predicted 56% adherence with the 2013 blood cholesterol guidelines in a retrospective analysis.In another study,Pokharelet al[7]evaluated trends in the use of statin therapy and non-statin therapy in cardiology practices,before and after the publication of the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines.They found modest,yet significant increases in the use of moderate-to high-intensity statins in ASCVD patients and no change in the other statin benefit groups and nearly half of statin eligible patients did not receive a statin[7].By comparison,our real-world study demonstrated similar trends in that nearly half of statin eligible patients did not receive a statin.Furthermore,adherence to GDST by general internists tended to be lower(55.5%)when compared to patients who were also being managed by a cardiologist(61.4%),although this difference was not statistically significant.Hence,being evaluated by a cardiology specialist did not appear to have any additional impact on the use of GDST at our institution.

The literature also notes that different factors and patient characteristics affect implementation and use of GDST.Schoenet al[10]found that women and patients with diabetes were less likely to be treated optimally;and this in turn,could impact cardiovascular outcomes.In our study,there was a higher proportion of patients with clinical ASCVD and diabetes that were seen by the cardiologist.These patients also had lipid profiles that necessitated therapy.This may suggest that at our institution,higher risk patients needing further LDL-C reduction are appropriately being managed by cardiology specialists who are trained to address these complex situations.Furthermore,patients who were managed by the cardiologist achieved significantly lower LDL-C levels,which may translate to greater reduction in future coronary heart disease events[11].Further long-term studies of these patients may shed light on such outcomes.

Several other studies have reported similar trends in 2013 ACC/AHA guideline implementation,however,very little is known about the barriers to adherence.Cloughet al[12]found that although community-based physicians often accurately estimated risk,beliefs and approach to statin discussion varied and these variables had minimal impact on low rates of statin prescribing.An inter-professional approach using the patient-centered medical home model made no difference in guideline implementation within a primary care practice[12].It has been well established that it may take up to 17 years for evidence to be fully implemented into practice,which may explain the low statin use in the overall study cohort[13].More studies will need to be conducted to fully understand these barriers.However,a recent study has shown that since the publication of the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines(and subsequent 2018 guidelines),cholesterol levels and statin use have improved in the US[14].Future studies should be conducted to evaluate the long-term impact of the latest cholesterol guidelines on adherence to GDST[15].

Our study has several limitations including the short period of analysis,its retrospective design,and small sample size.As noted,studies have demonstrated that it may take up to 17 years for evidence to be fully implemented into practice[13],and therefore the period of analysis for our study[which occurred within 3 years(2016 to 2017)following guideline publication],may simply reflect the lag time between guideline publication and implementation.Furthermore,our study relied on the accuracy and completeness of physician documentation which may have impacted the determination of physician adherence to guideline recommendations.Our analysis does not account for other reasons why GDST was not implemented(e.g.,patient factors,physician attitudes towards prescribing,adverse reactions,and cost of therapy).Additionally,our study did not account for patient adherence to prescriber recommendations.Regardless of statin treatment,we obtained information from the lipid panel which may not have impacted high-risk cohorts but underestimated statin eligibility for other cohorts(e.g.,patient previously prescribed statin,but at the time of assessment patient may not have appeared to be eligible for statin therapy based on cholesterol results).

Table 2 Adherence to guideline-directed statin therapy and patient characteristics by group,n(%)

In conclusion,our study compared the use of GDST in patients managed by general internists and those co-managed by a cardiologist.As expected,patients with higher cardiac risk factors and co-morbidities were more likely to be co-managed by a cardiologist and placed on statin therapy.In terms of appropriate statin use based on guidelines,there was no statistical difference in proportion of patients receiving GDST between groups managed by general internists alone or co-managed with a cardiologist;however,there was a significantly greater use of statins in patients comanaged by a cardiologist.Overall,statin use in this population is comparable to what other studies have shown and highlights the need to design and implement strategies to improve prescriber adherence to GDST.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Statins have an important and well-established role in the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease(ASCVD).However,several studies have reported widespread underuse of statins in various practice settings and populations.

Research motivation

Review of relevant literature reveals opportunities for improvement in the implementation of guideline-directed statin therapy(GDST).

Research objectives

In this study,we aimed to examine the impact of cardiologist intervention on the use of statin therapy in the ambulatory setting.

Research methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients who had at least one encounter at the adult Internal Medicine Clinic(IMC)and/or Cardiology Clinic(CC)and who had an available serum cholesterol test performed.The 2 comparison groups were defined as:(1)Patients only seen by IMC;and(2)Patients seen by both IMC and CC.Baseline characteristics of subgroups were compared.

Research result

A total of 268 patients met the inclusion criteria for this study.Approximately,14%had clinical ASCVD,13% were current smokers,66% were diabetic,and 63% were hypertensive.Statin use was observed in 55% of the entire cohort,with moderateintensity statins being the most commonly prescribed.Overall,in the IMC-CC group,73.6% of patients were prescribed statin therapy compared to 50.7% of patients in the IMC group.There was no statistical difference in the use of GDST between groups.

Research conclusions

Our study compared the use of GDST in patients managed by general internists and those co-managed by a cardiologist.Overall,statin use in this population is comparable to what other studies have shown and highlights the need to design and implement strategies to improve prescriber adherence to GDST.

World Journal of Cardiology2020年8期

World Journal of Cardiology2020年8期

- World Journal of Cardiology的其它文章

- Oliver Wendell Holmes’1836 doctorate dissertation and his journey in medicine

- Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes of anatomic repair in congenitally corrected transposition of great arteries

- Forensic interrogation of diabetic endothelitis in cardiovascular diseases and clinical translation in heart failure

- Sympathetic nervous system activation and heart failure:Current state of evidence and the pathophysiology in the light of novel biomarkers

- Classic Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and cardiac transplantation-Is there a connection?