Emerging role of colorectal mucus in gastroenterology diagnostics

Hesam Ahmadi Nooredinvand, Andrew Poullis

Abstract Colonoscopy is currently the gold standard for diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and colorectal cancer (CRC). This has the obvious drawback of being invasive as well as carrying a small risk. The most widely used non-invasive approaches include the use of faecal calprotectin in the case of IBD and fecal immunochemical test in the case of CRC. However, the necessity of stool collection limits their acceptability for some patients. Over the recent years, there has been emerging data looking at the role of non-invasively obtained colorectal mucus as a screening and diagnostic tool in IBD and CRC. It has been shown that the mucus rich material obtained by self-sampling of anal surface following defecation, can be used to measure various biomarkers that can aid in diagnosis of these conditions.

Key Words: Colorectal mucus; Inflammatory bowel disease; Crohn's disease; Ulcerative colitis; Colorectal cancer; Faecal calprotectin

INTRODUCTION

The current gold standard for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and colorectal cancer(CRC) is ileocolonoscopy. This however is time consuming, expensive and carries a small risk.Unnecessary colonoscopies could be avoided if reliable non-invasive tests were available to diagnose these conditions.

Non-invasive approaches to measurement of inflammation include serum biomarkers such as Creactive protein (CRP) although this is not bowel specific. Stool calprotectin is bowel specific and is the best studied test[1 ] however necessity of collecting stool makes this unpopular with some patients[2 -4 ].

For CRC, fecal immunochemical test (FIT) is the most widely used non-invasive screening tool with a sensitivity and specificity of 79 % and 94 % respectively[5 ]. Similar to faecal calprotectin, an abnormal FIT prompts further investigations and assessment but is not a diagnostic test.

EMERGING ROLE OF COLORECTAL MUCUS

Over the recent years there has been emerging data looking at the use of non-invasive colorectal mucus sampling as a screening and diagnostic tool for IBD as well as CRC.

Colorectal mucus acts as an interface between colonic mucosa and gut content and is a recipient of cells released from the mucosal surface[6 ]. Some of these cells embedded in the colorectal mucus are excreted with faeces. This cell containing colorectal mucus can therefore be used for specific cell and biomarker detection[7 -9 ]. There is increasing understanding of the complex roles of the colorectal mucus. The mucus itself is a dilute, aqueous and viscoelastic secretion with specific proteins, the mucins, being the major component[10 ]. The role, composition, physiology and pathophysiology are outside the scope of this review and have recently been reviewed elsewhere[11 ]. This review will focus on the emerging role of colorectal mucus in diagnostics.

Colorectal mucus can be obtained during proctoscopy[7 ,8 ,12 ] however this has the obvious drawback of being invasive and therefore unfavorable as a screening tool. Up until recently there was no reliable non-invasive method for colorectal mucus sampling. Over the past few years, a novel technique has been developed based on self-sampling of mucus-rich material from the anal surface immediately following defecation.

The use of colorectal mucus as a source of biomarkers has been evaluated in several studies. In the setting of IBD diagnostics and monitoring and CRC diagnostics colorectal mucus has been shown to be a novel and useful medium.

The first study assessing non-invasively collected colorectal mucus compared 141 patients (58 patients with IBD, 50 patients with IBS and 33 healthy volunteers). The study participants were instructed to swab the external anal area immediately following defecation and samples were collected for cytological and Mucin 2 (MUC2 ) analysis. This was the first study ever to describe non-invasively collected cytology demonstrating large numbers of preserved inflammatory cells in IBD. Significant differences in MUC2 levels were identified in IBDvsnon-IBD groups raising the possibility that colorectal mucus was a useful diagnostic medium[9 ].

In a follow on study the performance of several biomarkers including calprotectin, eosinophilderived neurotoxin (EDN) and protein S100 A12 was evaluated in active IBD[13 ]. EDN is a major secretory protein of eosinophils and elevated levels of EDN have previously been detected in faeces of IBD patients[8 ]. S100 A12 is another granulocyte protein and it has previously been proposed that measurement of the level of S100 A12 in the faeces can help differentiate IBD from IBS[14 ,15 ].

Every day after chores and school, Reuben scoured11 the town, collecting the hessian nail bags. On the day the two-room school closed for the summer, no student was more delighted than Reuben. Now he would have more time for his mission.

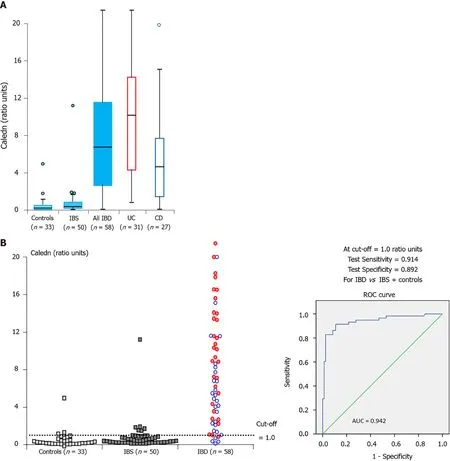

The authors found that the medium concentration of all of these biomarkers were significantly higher in IBD patients compared to inflammation free individuals with calprotectin and EDN being more sensitive than S100 A12 in detecting patients with IBD. Using a combined test taking into account the result of calprotectin and EDN (designated as CALEDN) resulted in sensitivity and specificity of 91 %and 89 % respectively in detecting patients with IBD (Figure 1 ). The concentration of all of these biomarkers was significantly higher in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients than those with Crohn’s disease(CD) with the most pronounced difference seen for EDN. Over a follow up period of 30 d following treatment there was a steady decrease of all biomarker levels among patients who demonstrated clinical improvement however correlation was easier to detect in UC patients[13 ].

Further to the description of inflammatory cells in the colorectal mucus of IBD patients an additional follow on cytology study demonstrated that true diagnostic cytology could be carried out on noninvasively collected colorectal mucus. Using cytology and immunocytochemistry a number of different cell types were identified (neutrophils, plasma cells and erythrophagocytes). Blinded cytological analysis enabled an accurate diagnosis to be made in 61 .8 % of cases[16 ].

Figure 1 Box and whisker plot and individual result distributions and receiver operating characteristic curve for the combined CALEDN test at stage 1 of the study. In the panel within the inflammatory bowel disease group, blue and red circles correspond to Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis cases, respectively. AUC: Area under the curve; IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; CD: Crohn’s disease; UC: Ulcerative colitis. Citation: Loktionov A, Chhaya V,Bandaletova T, Poullis A. Inflammatory bowel disease detection and monitoring by measuring biomarkers in non-invasively collected colorectal mucus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017 ; 32 : 992 -1002 . Copyright? The Authors 2017 . Published by John Wiley and Sons. A: Box and whisker plot; B: Receiver operating characteristic curve.

Given the success of this new medium in the diagnosis and monitoring of IBD attention has turned to CRC diagnostics. A pilot study was performed looking at whether various biomarkers detected in the colorectal mucus can be reliably used to aid detection of CRC. The diagnostic performance of 24 biomarkers were evaluated. 17 CRC and 35 healthy controls were used to assess these biomarkers.Quantification of haemoglobin, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1 ), M2 -pyruvate kinase(M2 -PК), peptidyl arginine deiminase-4 (PADI4 ), CRP, matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9 ), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), EDN and calprotectin all showed good diagnostic potential[17 ].

A larger follow on study with 35 healthy volunteers, 62 CRC-free symptomatic patients and 40 CRC patients was conducted to assess the utility of these biomarkers collected in colorectal mucus[18 ].

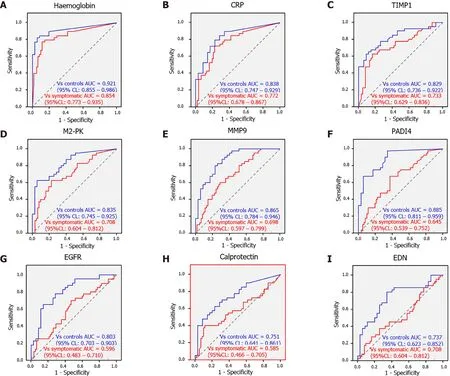

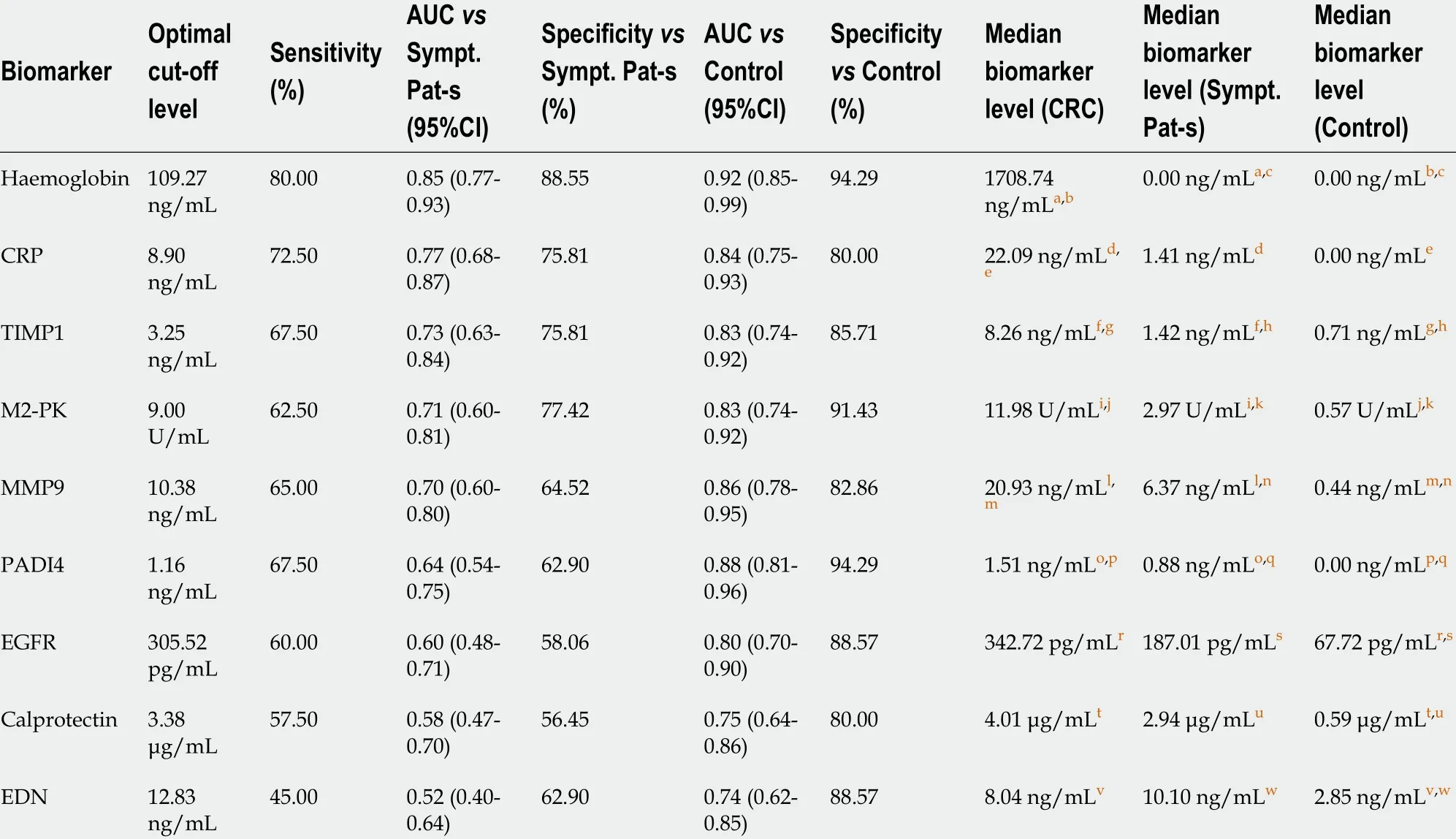

The sensitivity and specificity of each of these biomarkers was analyzed in two different scenarios.For assessment of these markers in bowel cancer screening (BCS) comparison was made between the CRC group and healthy controls “screening” arm. A “triage” arm to the study was set up to reflect non-BCS clinical practice and a comparison between CRC cases and symptomatic CRC free patients.Hemoglobin was the best performer with overall sensitivity of 80 % and specificity of 94 % and 85 .5 % in the ‘screening’ and the ‘triage’ group respectively. These values are comparable to those reported for CRC screening by FIT test[19 ]. All other biomarkers had a lower sensitivity and specificity especially in the triage group. Of note proximal CRC was associated with higher numbers of false-negative results.EGFR, calprotectin and EDN were worst performing and could not be recommended as reliable diagnostic markers (Table 1 and Figure 2 ).

Figure 2 Receiver operating characteristic curves for ‘screening’ (blue) and ‘triage’ (red) settings for haemoglobin, C-reactive protein,tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 , M2 -pyruvate kinase, matrix metalloproteinase 9 , peptidyl arginine deiminase-4 , epidermal growth factor receptor, calprotectin and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin. A: Haemoglobin; B: CRP; C: TIMP1 ; D: M2 -PK; E: MMP9 ; F: PADI4 ; G: EGFR; H:calprotectin; I: EDN. Citation: Loktionov A, Soubieres A, Bandaletova T, Francis N, Allison J, Sturt J, Mathur J, Poullis A. Biomarker measurement in non-invasively sampled colorectal mucus as a novel approach to colorectal cancer detection: screening and triage implications. Br J Cancer 2020 ; 123 : 252 -260 . Copyright? The Authors 2020 . Published by John Wiley and Sons.

Through the use of a questionnaire we found that the method of colorectal mucus sampling was generally very well accepted by the patients arguing that non-invasive testing of colorectal samples for haemoglobin can present an attractive alternative to FIT. The average time taken for carrying out the sampling was about six minutes. Given the immunochemical colorectal mucus sample testing for haemoglobin differs very little from faecal sample testing and the cost being similar to that of FIT, this alternative may boost participation rates.

CONCLUSION

These studies demonstrate that diagnostically informative cells can be obtained from colorectal mucus which can be non-invasively obtained by simply swabbing the external anal area immediately following defecation. The proposed method of colorectal mucus sample collection eliminates the necessity of stool collection and appeared to be very well accepted by the study participants with the vast majority of samples being suitable for biomarker and cytological analysis.

Future work however needs to focus on direct head-to-head comparison between stool calprotectin and colorectal mucus calprotectin in the case of IBD and colorectal mucus haemoglobin concentration and FIT test for colonic cancer screening.

Table 1 Comparison of tested colorectal mucus biomarker performance for colorectal cancer detection versus groups of asymptomatic control subject and patients with abdominal symptoms (based upon receiver operating characteristic curve analysis)

The non-invasive collection of colorectal mucus is a novel and exciting area of gastrointestinal diagnostics and may dramatically change our approach to the investigation and diagnosis of colorectal diseases.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Nooredinvand HA drafted the manuscript; Poullis A proofread and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4 .0 ) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4 .0 /

Country/Territory of origin:United Кingdom

ORCID number:Hesam Ahmadi Nooredinvand 0000 -0003 -3645 -2431 ; Andrew Poullis 0000 -0003 -0703 -0328 .

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies:British Society of Gastroenterology.

S-Editor:Fan JR

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Yu HG

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年12期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年12期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Epidemiology of stomach cancer

- Spinal anesthesia alleviates dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis by modulating the gut microbiota

- Near-infrared fluorescence imaging guided surgery in colorectal surgery

- Epidemiological, clinical, and histological presentation of celiac disease in Northwest China

- Microbiologic risk factors of recurrent choledocholithiasis postendoscopic sphincterotomy

- Similarities, differences, and possible interactions between hepatitis E and hepatitis C viruses: Relevance for research and clinical practice