Upper arm length along with mid- upper arm circumference to enhance wasting prevalence estimation and diagnosis:sensitivity and specificity in 6–59- months- old children

Mouhamed Barro , Mohamed Daouda Baro, Djibril Cisse, Noel Zagre, Thierno Ba, Shanti Neff Baro, Yacouba Diagana

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Wasting is a major public health problem in low- income and middle- income countries (LMIC). The risk of death is higher in wasted children defined by a weight- for- height Z- score (WHZ) below?2, when compared with non- wasted children.1When diagnosed with wasting,children can be treated at home.2The earlier the child is diagnosed, the shorter the duration of the treatment.3However,wasting screening and diagnosis has been a challenge for the entire humanitarian community. WHZ remains difficult to obtain routinely at the community level as it requires heavy equipment and welltrained staff. Mid- upper arm circumference (MUAC) is therefore preferred in the field due to its simplicity (MUAC <115 mm for severe wasting, MUAC <125 mm for wasting) as per the WHO recommendations.1However, MUAC has shown its limits for wasting diagnosis as well as prevalence estimation.

In 2019, wasting (as defined by WHZ score below ?2) affected more than 47 million children under 5 years old world- wide.4Although both low WHZ and MUAC are recommended for wasting diagnosis, only low WHZ is used for wasting prevalence evaluation by WHO.14The use of current WHO’s MUAC cut- off recommendation does not allow for wasting prevalence estimation with an acceptable accuracy.5

Different MUAC cut- offs have been proposed in the past decades for wasting diagnosis (also called acute malnutrition). In the 1960s, a study based on a population of non- malnourished Polish children showed that MUAC had little or no relation to age and gender in children aged 1–5 years.6Shakir and Morley suggested a coloured cord to measure upper- arm circumference for screening and diagnosis of wasting in children 6–59- months old.7Children were categorised in three groups according to their MUAC: red, yellow and green for MUAC under 125 mm, between 125 mm and 135 mm, and over 135 mm, respectively. In 1985,Lindtjorn showed that these cut- off points greatly exaggerate wasting prevalence rates and proposed new cut- off points (110 and 130 mm).8Benr and Nathanail compared the WHZ

We therefore considered an alternative method for wasting prevalence estimation, as well as wasting diagnosis with greater sensitivity and greater potential for routine use. Children’s height or age is not required.The method is based on the use of MUAC in relation to child’s upper arm length (UAL) which can be measured at the same time as the MUAC measurement,using the same MUAC tape. We tested this method in a nutritional survey conducted in July 2015 according to the methodology ‘Standardised Monitoring and Assessment of Relief and Transitions’ (SMART) in Mauritania. The current study aimed at evaluating the added value of the use of UAL along with the MUAC to diagnose and estimate the prevalence of wasting in comparison to the WHO standard as well as other MUAC based methods.

METHODOLOGY

Data collection

Data collected from the national SMART survey conducted in Mauritania in 2015 were used for the present study.16It was a cross- sectional survey with twostage random sampling, led by the nutrition department of the Ministry of Health with technical support from UNICEF. The survey followed SMART survey’s guideline.17All the measurements were carried out by teams of trained investigators who were experienced in taking anthropometric measurements. A national representative sample of children under 5 years old was used for this survey.

Weight was measured with a precision of 100 g using an electronic SECA- type weighing scale. Height was measured in centimetre with a precision of 0.1 cm using SHORR toises. MUAC was collected in all children aged 6–59 months with precision to 1 mm using MUAC tapes.UAL was measured by the same MUAC tape as those used for MUAC measurement. This length corresponds to that used to determine the mid- upper arm location, namely the length between the tip of the elbow (the olecranon)and the tip of the scapula (acromion). The oedema was systematically searched at the top of both feet by exerting a pressure with the thumb for 3 s. Standardisation of the measurements and plausibility checks were done according to the standards and recommendations of the SMART methodology.17

Data analysis

After a double entry to clean the anthropometric data,Z- scores were calculated using Emergency Nutrition Assessment (ENA) Delta software November 2014.Children were excluded from the analysis based on the following criteria: MUAC, height, sex or weight not recorded; extreme WHZ (+5); or arbitrarily considered extreme UAL (<7 cm or >30 cm). Wasting by low WHZ was defined by (WHZ

Wasted children (according to the WHZ

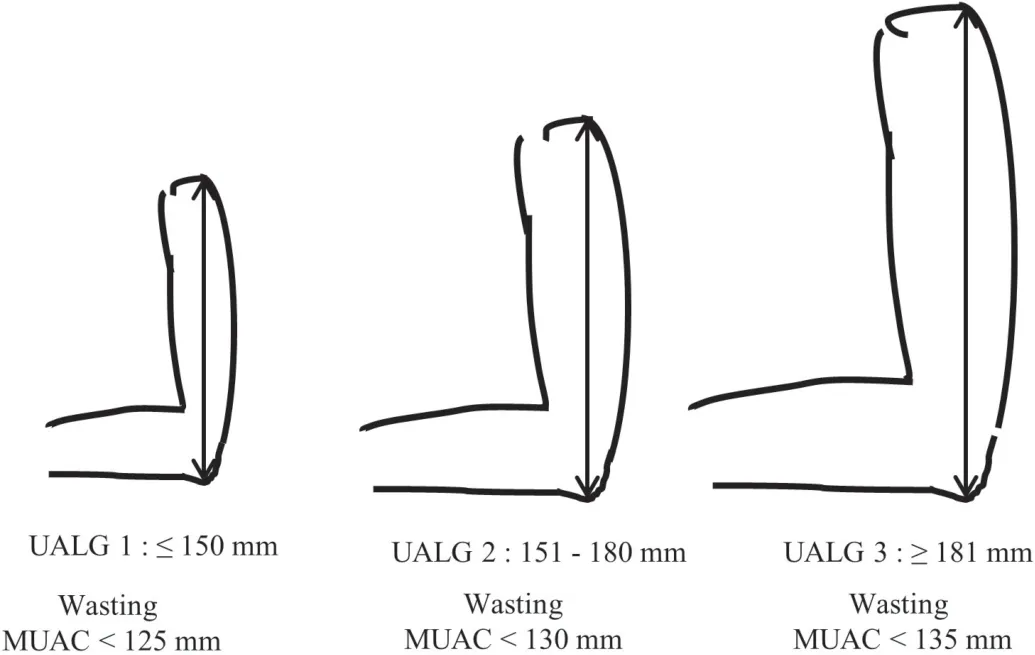

Figure 1 Classification of children according to their UAL and MUAC cut- off for each UALG. MUAC, mid- upper- arm circumference; UALG, upper arm length group.

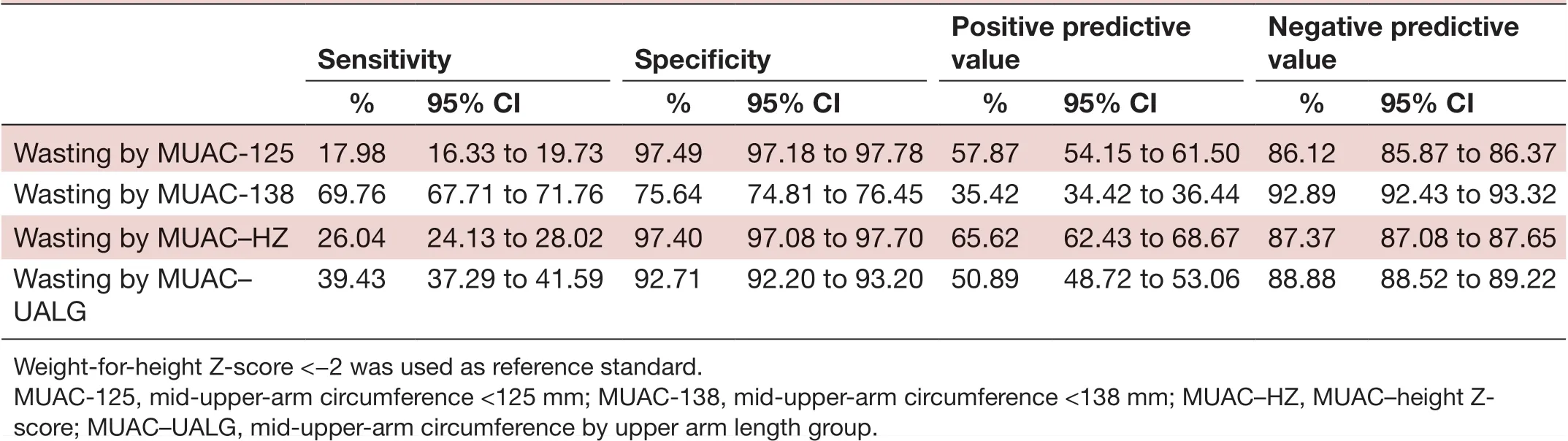

The accuracy of our diagnosis method was evaluated according to the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) recommendations.19Wasting by WHZ ?2.Medcalc online version (https://www. medcalc. org/ calc/diagnostic_ test. php) was used to calculate sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), with 95% CI for each wasting diagnosis method.

Statistic tests

Mean and SD were calculated for continuous values.Correlations between continuous variables were evaluated using Pearson test. Mean UAL, MUAC, age, height and WHZ comparison among UAL groups was performed by Student’s t- tests. Wasting prevalence was calculated for each wasting diagnostic method.

This analysis does not require ethical committee approval because the data are anonymous. A steering and ethics committee has been set up by the Ministry of Health and UNICEF to validate the protocol of the survey, including the ethical aspects relating to the care of severely malnourished children detected during the field survey.

RESULTS

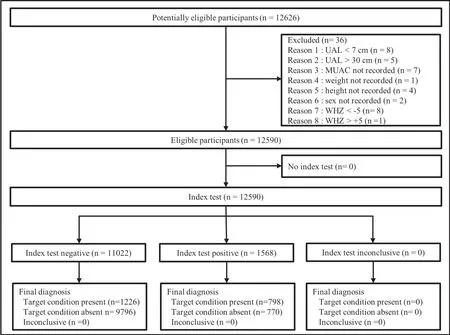

Anthropometric measurements were taken from 12 626 children aged 6–59 months throughout Mauritania. In total, 36 children (<0.29%) presenting missing or inaccurate data were excluded from analysis (figure 2). A total of 12 590 children with 49.9% girls were included in this study. No child was found with bilateral oedema during the survey.

Figure 2 Flow of participants for wasting diagnosis test. Children with not recorded MUAC, weight, height or sex were excluded. Children with too high or too low UAL were excluded. MUAC, mid- upper arm circumference; UAL, upper arm length;WHZ, weight- for- height Z- score.

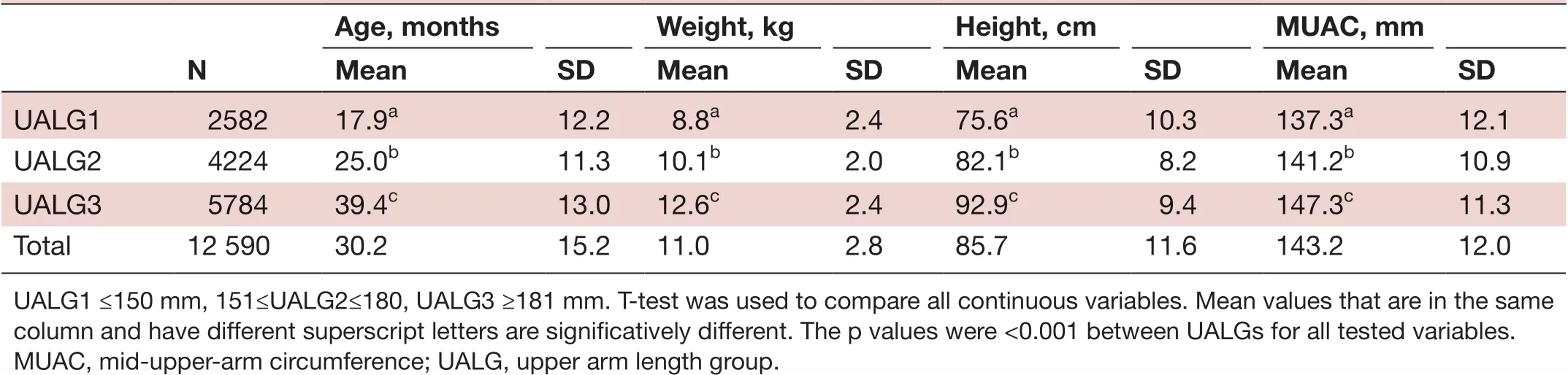

TabIe 1 Anthropometric measurements by UALG

Our results demonstrated that UAL was correlated to height (Pearson correlation=0.65, p<0·001) and age(Pearson correlation=0.62, p<0.001) and MUAC was correlated to age (Pearson correlation=0.45, p<0.001) as well as height (Pearson correlation=0.51, p<0.001).

Using ROC curves with WHZ as reference standard,new MUAC cut- offs (for wasting diagnosis) were determined for each UALG: 125 mm, 130 mm and 135 mm for UALG1, UALG2 and UALG3, (figure 1 and online supplemental figure 1).

The mean and SD of children's’ age, weight and MUAC are described in table 1.

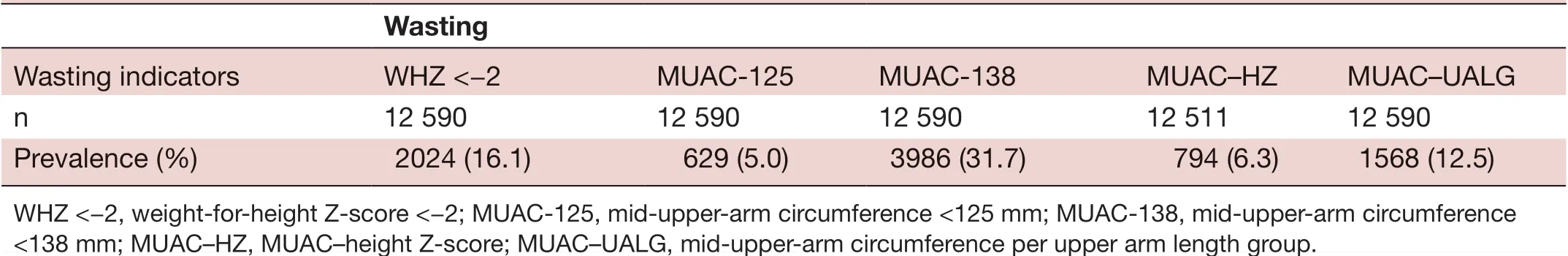

Mean MUAC, height and age significantly increased with UALG (p<0.001) (table 1). The prevalence of wasting as determined by WHZ

The diagnosis test accuracy for each indicator is summarised in the table 3. Overall, MUAC-125 had the lowest sensitivity (17.98% (16.33%; 19.73%)) and the highest specificity (97.49% (97.18; 97.78)) (table 3). With single fixed cut- off indicators (MUAC-125 or MUAC-138)sensitivity decreases, and specificity increases with UALG.This was not observed with adapted cut- offs (MUAC–HZ or MUAC–UALG) (online supplemental table 1).Although MUAC-138 had the highest sensitivity (69.76%(67.71; 71.76)), it had the lowest specificity (75.64%(74.81; 76.45)) leading to more than 24% false positives.MUAC–UALG had a higher sensitivity (39.43% (37.29;41.59)) than MUAC-125 and MUAC–HZ. MUAC–UALG had a higher specificity than MUAC-138 and a lower specificity than MUAC–HZ and MUAC-125.

MUAC-125 had a lower PPV (57.87% (54.15; 61.50))than MUAC–HZ (65.62% (62.43; 68.67)) and a lower NPV than that of all other indicators. MUAC-138 had the lowest PPV (35.42% (34.42; 36.44)) although the NPV was the highest among the indicators (92.89% (92.43;93.32)).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated two principal results related to the use of MUAC–UALG.

First, the use of UAL along with MUAC enhanced wasting prevalence estimation (table 2). Wasting prevalence evaluated by MUAC–UALG was the closest to that of WHZ

TabIe 2 Wasting prevalence determined by different methods

TabIe 3 Wasting diagnosis accuracy based on sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value for each indicator

Second, the use of UAL in combination with MUAC enhanced the wasting diagnosis accuracy. We selected MUAC cut- offs for each UALG in such a way to minimise the number of false positives (online supplemental figure 1). Higher sensitivity could be obtained by selecting higher MUAC cut- offs for each UALG, but we believe that this approach would have a negative impact on the malnutrition management system. Although the whole community needs nutrition interventions, those who are malnourished need it more. In our study, around 82% (1- sensitivity) of children with WHZ

The study was conducted in the Mauritanian population which is not representative of the world population.However, a multicentric study in different populations is feasible given the simplicity of collecting children’s UAL. WHZ was used as a reference standard for this study although this index is only a proxy for wasting.The overlap ratio between WHZ and MUAC varies by country.5However, WHZ is widely used and accepted for wasting prevalence estimation around the world by the WHO. A more specific wasting diagnosis tool is needed in the future to compare with MUAC–UALG. Other alternative approaches could be used to evaluate the accuracy of MUAC–UALG method to identify more vulnerable children. Thus, MUAC–UALG mortality and or morbidity prediction capacity, and its association with wasting clinical biomarkers among children with low grade inflammation status could be considered.

At the community level, compared with the WHZ method, it is easier to use the MUAC–UALG which does not require any investment in equipment to measure height and weight. Measuring height and weight can be a challenge in emergency settings such as in COVID-19 context. The portability of the MUAC tape is an advantage for its adoption by community health workers. The cost is also much lower than a scale measuring height and weight. Three MUAC tapes with different cut- offs according to UALG can be used by community health workers in the field for wasting diagnosis.

This study is aligned with the Council of Research and Technical Advice on Acute Malnutrition(CORTASAM) recommendations regarding the priority research.22Indeed, CORTASM group has recognised that the current MUAC admissions criteria for wasting (MUAC- 15mm) does not select for all high- risk children, leaving behind some children who would be diagnosed as wasted by WHZ or WAZ methods. More research is needed concerning the options available to identify these high- risk children and ensure successful diagnosis and treatment, but the MUAC–UALG method is a promising candidate.

To the best of our knowledge, the use of UAL in wasting diagnosis has never been proposed. This method does not add any additional tasks to the diagnostic process and has the potential to improve it.This method could be adopted in the field as a part of monitoring nutritional status of children and as an admission criterion in community- based management of acute malnutrition. Like MUAC–height or MUAC–age Z-score, future studies aimed at the creation of a MUAC–UAL Z- score should be considered. Using UAL- for- age Z- score could also be considered as a substitute for the height- for- age method in diagnosing cases of chronic malnutrition. Indeed, UAL is simpler and less expensive than height measurement.A comparison of each child’s UAL with a same age and sex reference population could be considered for stunting diagnosis. Thus, in nutrition programmes,weight- for- age monitoring could be supplemented with UAL- for- age in cases where children’s height is not known.

Beside wasting, obesity is also a major concern even in LMIC.4Increasing the MUAC cut- off for wasting diagnosis for all children could have a negative impact if many non- wasted children are treated. It could also prevent those in need to get enough supplements in an event of shortage. Our data showed that 7.9% of children were considered as wasted despite having a WHZ >?1 when MUAC <138 mm is used. With MUAC–UALG this percentage drops to 2.2%.

CONCLUSION

Wasting diagnosis with a fixed cut- off MUAC has limitations that can be mitigated using MUAC- for- height and MUACfor- age indicators. The complexity of accurately collecting age and height in the field makes MUAC–UALG a good alternative for wasting diagnosis and prevalence estimation.MUAC–UALG could be used in emergency settings such as in COVID-19 context. The sensitivity is improved without compromising the specificity. Thus, using UAL along with MUAC enhances the accuracy of wasting diagnosis and the estimation of wasting prevalence. Future studies involving data from more children in different regions may lead to new perspectives on the use of MUAC–UALG as an anthropometric measure to diagnose wasting in developing countries. We recommend the inclusion of arm length in every national nutritional survey to collect more data for a multicentric study.

AcknowledgementsWe would like to thank all participants and all investigators for their effort in data collecting.

ContributorsMDB and MB contributed in the article equally. They designed,approved and are accountable for the work, MDB more specifically conducted the field study, carried out the data editing contributed to the design of the study, the statistical analyses, the writing of the manuscript and the coordination of coauthor inputs (study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing). MB contributed to the design of the study conducted the statistical analyses, produced the tables and graphs, reviewed the documentation, the integration of the different inputs and the writing of the manuscript (figures, study design, data collection,data analysis, data interpretation, writing). DC and NZ participated in the analysis of the results and the interpretation of the data. TB and SNB has done a complete review of the statistical analyses of the data and tables of the results. YD reviewed the documents and provided an external perspective on the concept, analysis,interpretation and conclusions of the article (revising it critically for important intellectual content).

FundingThe authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not- for- profit sectors.

Competing interestsMB works for Nutriset S.A.S, Malaunay, France. This study started before he joined the company and is independent to his activity at the company. No other author has a conflict of interest related to this study.

Patient consent for publicationNot required.

Provenance and peer reviewNot commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statementData are available upon reasonable request by email to the corresponding author.Supplemental materialThis content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer- reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines,terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Open accessThis is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY- NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non- commercially,and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non- commercial. See: http:// creativecommons. org/ licenses/ by- nc/ 4. 0/.

ORCID iD

Mouhamed Barro http:// orcid. org/ 0000- 0003- 1731- 4447

Family Medicine and Community Health2021年2期

Family Medicine and Community Health2021年2期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- One size does not fit all: adapt and localise for effective, proportionate and equitable responses to COVID-19 in Africa

- Rationales and uncertainties for aspirin use in COVID-19: a narrative review

- Practical recommendations for the prevention and management of COVID-19 in low- income and middleincome settings: adapting clinical experience from the field

- Paediatric primary care in Germany during the early COVID-19 pandemic:the calm before the storm

- Do statins reduce mortality in older people? Findings from a longitudinal study using primary care records

- Communities and service providers address access to perinatal care in postconflict Northern Uganda:socialising evidence for participatory action