lmpact of psychosocial comorbidities on clinical outcomes after liver transplantation:Stratification of a high-risk population

Neil Bhogal,Amaninder Dhaliwal,Elizabeth Lyden,Fedja Rochling,Marco Olivera-Martinez

Neil Bhogal,Amaninder Dhaliwal,Fedja Rochling,Marco Olivera-Martinez,Department of Internal Medicine,Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology,University of Nebraska Medical Center,Omaha,NE 68198,United States

Elizabeth Lyden,Department of Biostatistics,Division of Public Health,University of Nebraska Medical Center,Omaha,NE 68198,United States

Abstract

Key words: Liver transplantation;Recidivism;Psychosocial decompensation;Noncompliance;Transplant psychiatry

INTRODUCTION

Liver transplantation is the accepted standard of care for end-stage liver disease due to a variety of etiologies including decompensated cirrhosis,fulminant hepatic failure,and primary hepatic malignancy[1].The number of liver transplantations is increasing in the United States with over 33000 procedures performed in the last five years[2].In addition,more organs are available for transplantation with practice changes such as human immunodeficiency virus,hepatitis B and C infected donor grafts,and living donor donations[3-5].Also,the landscape is changing regarding liver transplantation in severe alcoholic hepatitis given studies showing favorable outcomes[6,7].Despite these advances,as of January 2019 there are currently over 13000 candidates on the liver transplant waiting list emphasizing the importance of rigorous patient selection[8].

The liver transplantation process requires a multi-disciplinary approach that facilitates collaboration between different specialties including hepatologists,transplant surgeons,neuropsychologists,psychiatrists,social workers,and ethics committees.There are evidence-based criteria involving the degree of end-organ damage and decompensation required prior to being listed for transplant as organ allocation is based on the model for end-state liver disease score[9].However,a growing emphasis has been placed on the psychosocial status of patients prior to liver transplantation.The psychosocial assessment of a patient is a critical aspect of the evaluation process prior to being listed for liver transplantation.There is minimal data assessing post-transplant outcomes in patients after they have received a liver transplant that were characterized as having psychosocial problems prior to being evaluated and listed for transplantation.

Despite the aforementioned practice changes,there are still a limited number of organs available for transplantation.Thus,a successful outcome depends upon a complete evaluation[10].Liver transplant centers have various predefined criteria that must be met prior to being listed including minimum time of documented sobriety in the case of alcoholic liver disease and range of body-mass index for obese patients[11,12].In contrast,there are no standardized criteria for selection for transplant in respect to psychosocial comorbidities,and there are no evidence-based guidelines for screening or treatment prior to listing[13].Psychiatric disorders and polysubstance abuse are common amongst transplant candidates[14].Previous studies have indicated that several psychosocial morbidities can lead to adverse outcomes after liver transplantation[15].Not only can there be an impact on morbidity and mortality but also a decrease in the quality of life[16].Most of the previous studies have focused on psychiatric comorbidities,specifically major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety[17-19].There are few studies regarding the impact of additional psychosocial barriers to liver transplant including financial hardship,lack of caregiver support,polysubstance abuse,and issues with medical non-compliance.The purpose of our study was to assess the impact of certain pre-transplant psychosocial comorbidities on outcomes after liver transplantation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective analysis was performed on all patients older than 18 years of age at our institution who underwent liver transplantation over a five-year span from 2012-2016.Approval for the project was obtained by The University of Nebraska institutional review board (protocol 304-17-EP).Demographic data,etiology of liver disease,psychosocial,and psychiatric history were collected on all patients.Patients determined to have psychiatric disease were individuals with a known psychiatric diagnosis who followed with a mental health professional or utilized a psychiatric medication within 12 mo of organ transplant.

Additional data was gathered regarding specific treatment of psychiatric disorders prior to organ transplantation including medications and psychotherapy.Finally,psychosocial comorbidities including documented medical non-compliance,polysubstance abuse,financial issues,and lack of caregiver support were collected.These parameters were ascertained by reviewing the pre-transplant evaluation records including outpatient multi-disciplinary transplant clinic visits,inpatient hospitalization notes,and documentation from patient selection meetings.Medical non-compliance was determined by transplant committee review documenting concerns for adherence to pre-transplant recommendations.For polysubstance abusespecific agents documented included alcohol,marijuana,cocaine,methamphetamines,heroin,prescription opioids,and prescription benzodiazepines.The methods of detection were serum for ethanol and urine drug screen for the other substances.

The primary outcome assessed post-transplantation was survival.Secondary outcomes measured include graft failure,biopsy proven episodes of acute rejection,psychiatric decompensation defined as the requirement of a psychiatric consultation or new medication,number of readmissions,presence of infection necessitating contact with a healthcare professional,recidivism for alcohol and other substances,and documented caregiver support failure.These outcomes were obtained after reviewing transplant specific electronic medical documentation in the post-transplant period including inpatient records,clinic documentation,and telephone encounters.The databases reviewed that are in use by our institution include Epic electronic medical record and OTTR transplant management system.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (counts and percentages,means,standard deviations,medians,minimums,and maximums) were used to summarize the data.Graft failure,psychiatric decompensation,presence of infection,and recidivism were measured in a binary fashion.Acute rejection episodes and readmissions were measured as continuous variables.Fisher’s exact test was used to look at associations of categorical variables.The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the number of hospitalizations between the groups.This nonparametric equivalent of the twosamplet-test was used due to the skewness of the data.AP-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.All statistical analysis was performed by Elizabeth Lyden,a professional statistician in the department of biostatistics in The College of Public Health at The University of Nebraska Medical Center.

RESULTS

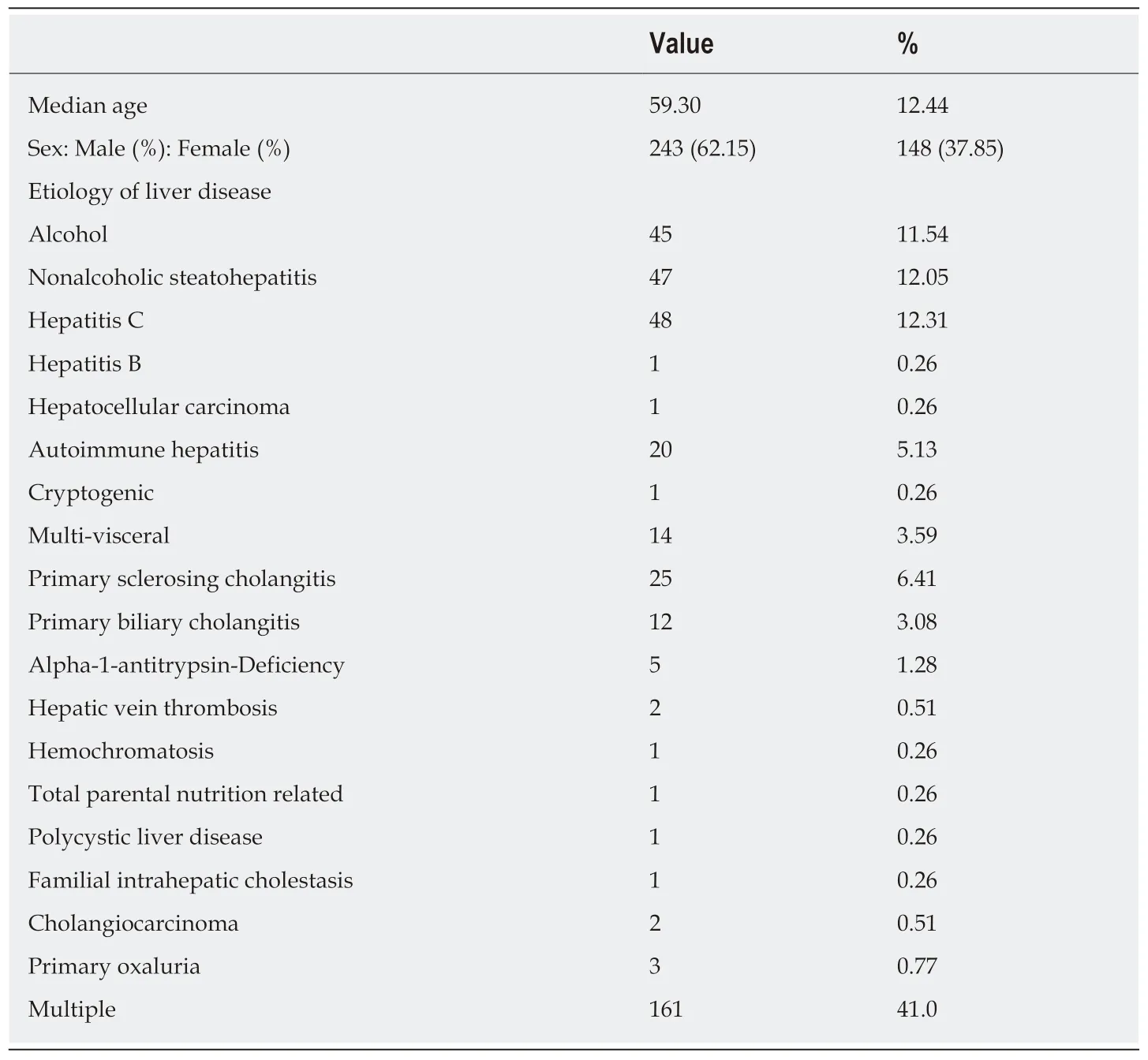

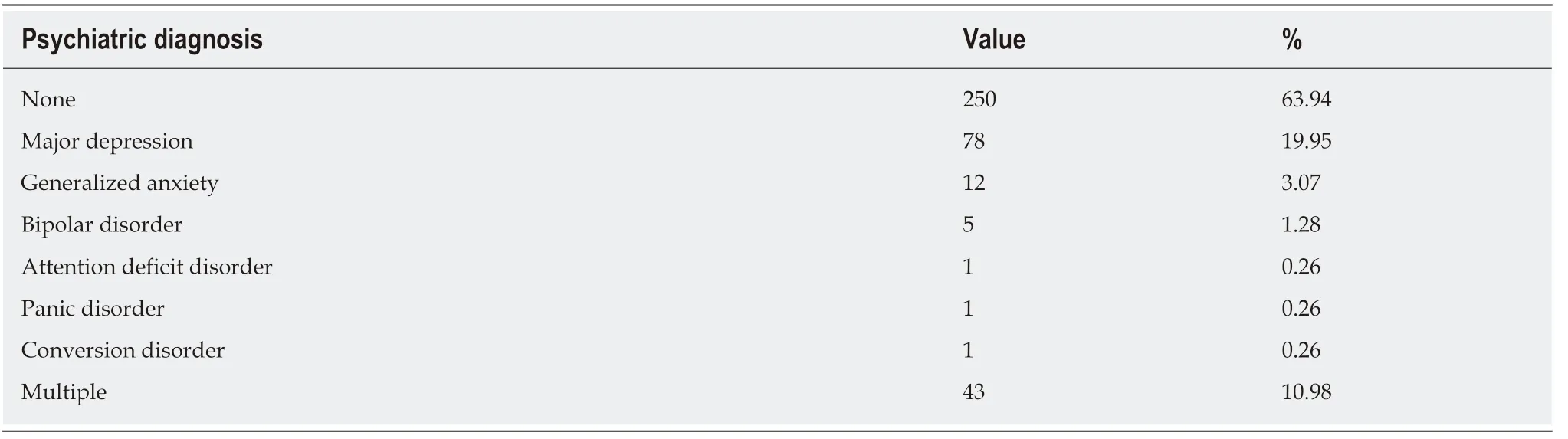

Our analysis included 391 patients.Demographic data including age,sex,and etiology of liver disease are summarized in Table 1.The median age of patients undergoing liver transplant was 59 years old (standard deviation:12.44).Our study included 243 males (62.2%) and 148 females (37.8%).The most common indications for liver transplantation were decompensated cirrhosis secondary to chronic hepatitis C virus (n =48,12.3%) followed by non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (n =47,12.1%)and alcoholic liver disease (n =45,11.6%).There were 141 patients (36.1%) with a history of psychiatric disease.Data regarding psychiatric history is summarized in Table 2.The most common psychiatric diagnosis was major depressive disorder (n =78,20%) followed by generalized anxiety disorder (n =12,3.1%).There were 92 patients (23.5%) who received therapy for their psychiatric disorders prior to transplant.

There were additional psychosocial comorbidities evaluated in this patient population.These included documented history of financial hardship in the pretransplant evaluation,history of polysubstance abuse,history of documented noncompliance in the pre-transplant evaluation,and lack of caregiver support.The primary outcome evaluated was overall,30-d,and 1-year survival post-liver transplant.Secondary outcomes evaluated post-transplant included graft failure,episodes of graft rejection,psychosocial decompensation as previously defined,caregiver support failure,recidivism of alcohol and drug use,number of hospitalizations,and infections necessitating medical care.

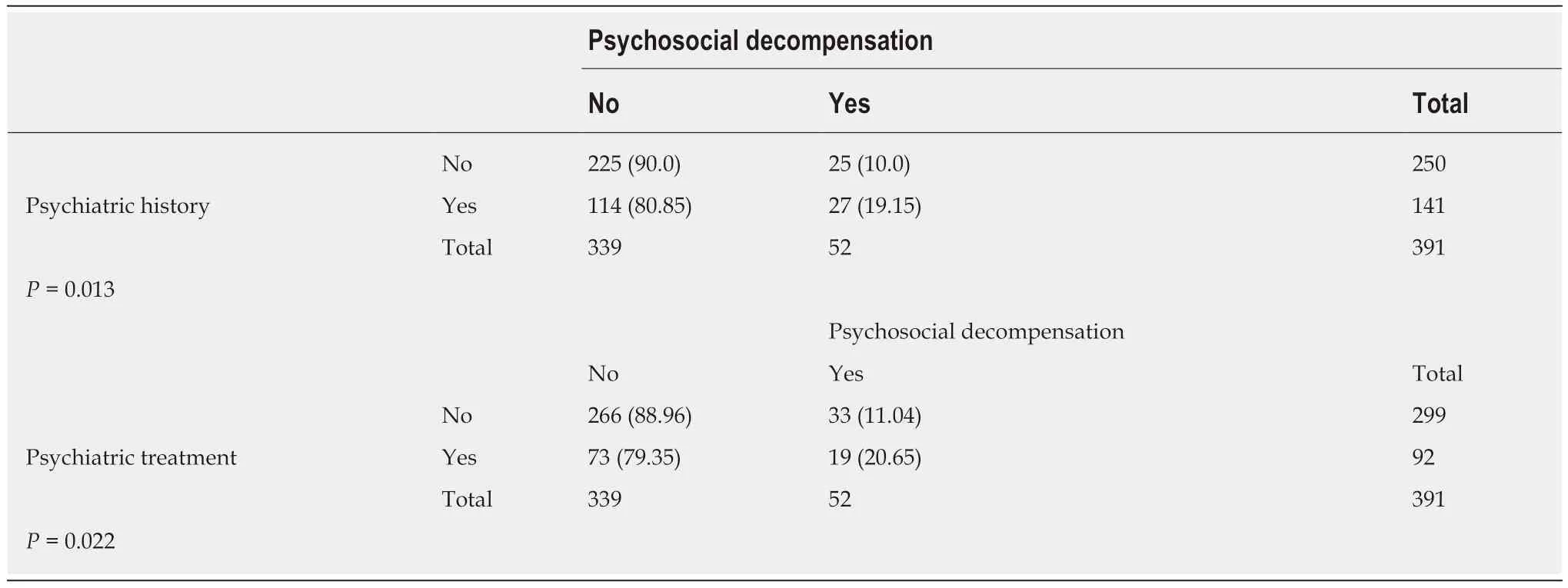

For the primary outcome,there were no differences in survival found in the variables compared including history of psychiatric disease,financial hardship,polysubstance abuse,documented compliance issues,or lack of caregiver support.In evaluation of the secondary outcomes,patients with a history of psychiatric disease had a higher incidence of psychiatric decompensation after liver transplantation (19%vs10%,P =0.013).Treatment of psychiatric disorders resulted in a reduction of the incidence of psychiatric decompensation (21%vs11%,P =0.022).These results are summarized in Table 3.

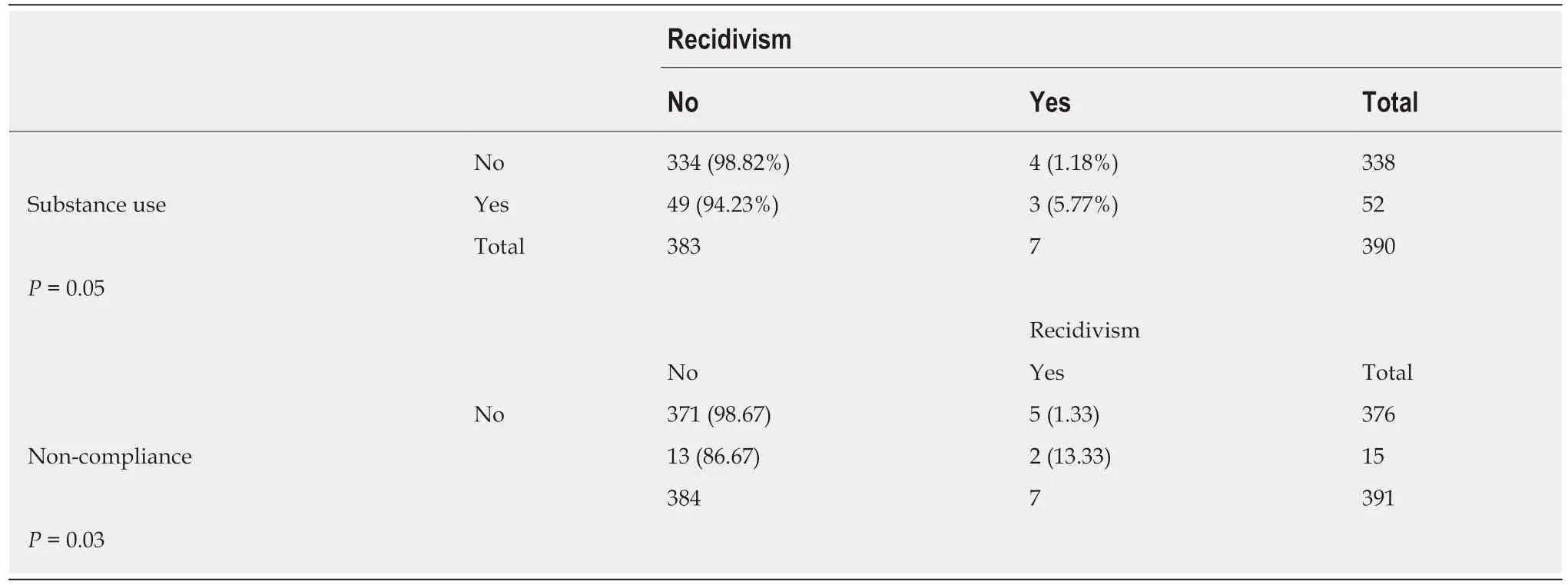

Patients with a history of polysubstance abuse in the transplant evaluation had a higher incidence of substance abuse after transplantation (5.8%vs1.2%,P =0.05).In this specific cohort,15 patients (3.8%) were found to have medical compliance issues in the transplant evaluation.Of this group,13.3% were found to have substance abuse after transplantation as opposed to 1.3% in patients without documented compliance issues (P =0.03).These results are summarized in Table 4.Finally,patients with a history of documented medical non-compliance in the pre-transplantation evaluation had a higher rate of graft failure as opposed to patients without compliance issues(60%vs32%,P =0.047).There were no other significant differences found in the other secondary outcomes evaluated.These results are summarized in Table 5.

DISCUSSION

A liver transplantation is a high-risk endeavor and thus requires a thorough medical and psychosocial evaluation.Although we did not find any difference in regard to the primary outcome of survival,we believe this study adds to the literature that psychosocial comorbidities have a significant impact on outcomes in liver transplantation as certain psychosocial entities were associated with worse outcomes after liver transplantation.Patients with documented non-compliance in the pretransplant evaluation had worse outcomes after organ transplantation including a higher incidence of graft failure and recidivism.These findings have been previously seen in relation to renal transplantation but have not been previously documented in respect to liver transplantation to our knowledge[20].This represents a very high-risk population and further prospective and potentially multi-center work is required to create compliance guidelines prior to listing for transplantation.

Psychiatric disease commonly coexists with chronic liver disease with some estimates of up to 50% of patients with cirrhosis suffer from psychiatric disorders[21].Although previous studies have shown that major depression is associated with a decreased survival,our study did not corroborate these findings[14,16].However,our study did find that patients with psychiatric disorders are at higher risk of psychiatric decompensation after liver transplant regardless of how compensated their psychiatric disease status was prior to evaluation.In addition,our findings show that treatment of psychiatric disease was shown to decrease the incidence of psychiatric decompensation after transplantation and thus improve outcomes.This study substantiates several previous studies that psychiatric disorders affect outcomes after liver transplantation.As psychiatric disorders are commonly encountered in patients with end-stage liver disease,this represents a high-risk population.Further prospective studies are required to best optimally manage this group in the pre-transplant setting in order to improve outcomes after liver transplantation.

Table1 Demographic data

Our study has limitations associated with any retrospective analysis and is subject to confounding factors that were unable to be measured.In addition,the majority of our data was gathered from pre- and post-transplantation documentation thus imparting a level of provider subjectivity in determining certain variables such as psychiatric diagnoses,medical non-compliance,and issues with caregiver support.There is an inherent limitation in ascertaining data retrospectively.However,this is common practice during the transplantation evaluation thus emulating traditional practice.Regardless,this analysis adds valuable information to the growing literature regarding the importance of focusing on psychosocial comorbidities prior to liver transplantation confirming available data that this represents a high-risk population.Further prospective and potentially multi-center studies are warranted to properly determine appropriate guidelines for liver transplantation specifically regarding psychiatric disease,documented medical non-compliance,financial issues,and substance abuse.

Table2 Psychiatric history

Table3 Psychiatric decompensation

Table4 Recidivism

Table5 Graft failure

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Liver transplantation is the accepted standard of care for end-stage liver disease due to a variety of etiologies including decompensated cirrhosis,fulminant hepatic failure,and primary hepatic malignancy.There are currently over 13000 candidates on the liver transplant waiting list emphasizing the importance of rigorous patient selection.There are few studies regarding the impact of additional psychosocial barriers to liver transplant including financial hardship,lack of caregiver support,polysubstance abuse,and issues with medical non-compliance.We hypothesized that patients with certain psychosocial comorbidities experienced worse outcomes after liver transplantation.

Research motivation

There are certain accepted criteria to list patients for liver transplantation such as model for endstate liver disease score,age,and body-mass-index.Many patients with liver disease have significant psychosocial comorbidities that may impact outcomes after liver transplantation.There are no evidence-based guidelines regarding psychosocial aspects of the liver transplant evaluation.

Research objectives

The main objective of this study was to assess the impact of certain pre-transplant psychosocial comorbidities on outcomes after liver transplantation.We found that certain psychosocial comorbidities led to worse outcomes after transplantation.

Research results

For the primary outcome,there were no differences in survival.Patients with a history of psychiatric disease had a higher incidence of psychiatric decompensation after liver transplantation (19% vs 10%,P = 0.013).Treatment of psychiatric disorders resulted in a reduction of the incidence of psychiatric decompensation (21% vs 11%,P = 0.022).Patients with a history of polysubstance abuse in the transplant evaluation had a higher incidence of substance abuse after transplantation (5.8% vs 1.2%,P = 0.05).In this cohort 15 patients (3.8%) were found to have medical compliance issues in the transplant evaluation.Of these specific patients,13.3%were found to have substance abuse after transplantation as opposed to 1.3% in patients without documented compliance issues (P = 0.03).

Research conclusions

Patients with a history of psychiatric disease had a higher incidence of psychiatric decompensation.Treatment of psychiatric disorders led to a reduction of the incidence of psychiatric decompensation after liver transplantation.Patients with a history of polysubstance abuse and medical non-compliance had a higher incidence of substance use after liver transplantation.This study adds to the literature that this represents a high-risk population.Further multi-center and prospective studies are warranted to formulate evidence-based guidelines to assist in evaluating pa tients undergoing evaluation for liver transplantation.

Research perspectives

This study highlights the importance of the psychosocial evaluation in the liver transplantation process.

World Journal of Hepatology2019年8期

World Journal of Hepatology2019年8期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Fascioliasis presenting as colon cancer liver metastasis on 18Ffluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography:A case report

- Outpatient telephonic transitional care after hospital discharge improves survival in cirrhotic patients

- Prolonged high-fat-diet feeding promotes non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and alters gut microbiota in mice

- ls porto sinusoidal vascular disease to be actively searched in patients with portal vein thrombosis?