Clinical and prognostic implications of delirium in elderly patients with non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes

Miquel Vives-Borrás, Manuel Martínez-Sellés, Albert Ariza-Solé, María T. Vidán, Francesc Formiga,Héctor Bueno, Juan Sanchís, Oriol Alegre, Albert Durán-Cambra, Ramón López-Palop,

Emad Abu-Assi8, Alessandro Sionis1, LONGEVO-SCA Investigators

1Department of Cardiology, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Institute of Biomedical Research IIB Sant Pau, CIBERCV, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

2Department of Cardiology, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Mara?ón, CIBERCV, Universidad Complutense, Universidad Europea, Madrid, Spain

3Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain

4Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Mara?ón, IiSGM, CIBERFES, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain

5Hospital Doce de Octubre, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares, Madrid, Spain

6Hospital Clínico de Valencia, INCLIVA, Universidad de Valencia, CIBERCV, Spain

7Hospital Universitario San Juan, Alicante, Spain

8Hospital álvaro Cunqueiro, Vigo, Spain

Abstract Background Elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTE-ACS) may present delirium but its clinical relevance is unknown. This study aimed at determining the clinical associated factors, and prognostic implications of delirium in old-aged patients admitted for NSTE-ACS. Methods LONGEVO-SCA is a prospective multicenter registry including unselected patients with NSTE-ACS aged ≥ 80 years. Clinical variables and a complete geriatric evaluation were assessed during hospitalization. The association between delirium and 6-month mortality was assessed by a Cox regression model weighted for a propensity score including the potential confounding variables. We also analysed its association with 6-month bleeding and cognitive or functional decline. Results Among 527 patients included, thirty-seven (7%) patients presented delirium during the hospitalization. Delirium was more frequent in patients with dementia or depression and in those from nursing homes (27.0% vs. 3.1%, 24.3% vs. 11.6%, and 11.1% vs. 2.2%, respectively; all P < 0.05).Delirium was significantly associated with in-hospital infections (27.0% vs. 5.3%, P < 0.001) and usage of diuretics (70.3% vs. 49.8%, P =0.02). Patients with delirium had longer hospitalizations [median 8.5 (5.5-14) vs. 6.0 (4.0-10) days, P = 0.02] and higher incidence of 6-month bleeding and mortality (32.3% vs. 10.0% and 24.3% vs. 10.8%, respectively; both P < 0.05) but similar cognitive or functional decline. Delirium was independently associated with 6-month mortality (HR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.02-2.13, P = 0.04) and 6-month bleeding events (OR = 2.87; 95% CI: 1.98-4.16, P < 0.01). Conclusions In-hospital delirium in elderly patients with NSTE-ACS is associated with some preventable risk factors and it is an independent predictor of 6-month mortality.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndromes; Delirium; Prognosis; The elderly

1 Introduction

Elderly patients represent roughly one-third of all admissions for non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS),[1,2]and an increase in this proportion is foreseen in the coming years.[3]These patients frequently associate comorbidities such as dementia and frailty,[4]and they are known to have higher mortality,[1]and to receive less evidence-based treatments.[5]Therefore, identifying clinical predictors of worse outcomes in this specific population is mandatory.

Delirium is an acute disturbance of attention and cognitive functioning that frequently complicates hospitalization of old-aged patients.[6]Although this condition and its significance has been extensively studied in critical, medical,and even surgical care populations,[7-9]little is known about its frequency in elderly patients admitted for NSTE-ACS and its impact on their clinical evolution. Given that riskstratification tools for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) do not consider specific geriatric factors,[10,11]analysis of these conditions, such as delirium, may be of potential utility in clinical practice.

This study aimed to describe the clinical associated factors and the prognostic implications of delirium in a large multicenter cohort of unselected elderly patients; aged ≥80 years, admitted for NSTE-ACS.

2 Methods

2.1 Study population

The study population consists of 527 patients from the LONGEVO-SCA registry. The detailed study design and variables have been published previously.[12]Briefly, LONGEVO-SCA is a Spanish multicenter, prospective, observational study conducted between March 2016 and September 2016. We enrolled consecutive elderly patients admitted for NSTE-ACS in 44 tertiary and secondary hospitals. The inclusion criteria were: (1) age ≥ 80 years; (2) chest pain consistent with ACS; and (3) changes on ECG (negative T-wave or ST-segment decline) and/or elevation of myocardial damage biomarkers. The exclusion criteria were: (1) patient refusal to participate in the registry; and (2) impossibility of obtaining the geriatric tests. Patients with severe comorbidities were only excluded if symptoms of myocardial ischemia were clearly triggered only by other conditions, such as acute anemia, severe decompensated respiratory insufficiency, active infectious diseases or severe coexisting valvular disease (type 2 myocardial infarction). The inclusion in the study did not imply any change in patients’ clinical management; therefore, the medical treatment, the complementary examinations including the need for coronary angiography or the choice of stents were decided by the medical team. Informed consent was obtained from the patients or their next of kin. The study was approved by the ethics committees of each center and the investigation conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The project was supported and coordinated by the Section of Geriatric Cardiology, Spanish Society of Cardiology.

2.2 Study variables

Data were collected using specifically designed web forms (http://www.adknoma.com/LONGEVO-SCA), and quality controls were undertaken every month. We recorded the following clinical variables at study inclusion: (1) demographic and previous clinical history including comorbidities; (2) case history and physical examination; (3) ECG,laboratory blood test and echocardiography at admission; (4)coronary angiography and coronary angioplasty when performed; and (5) medical treatment and clinical evolution.Standard criteria were used to define each variable. Delirium was defined as an acute and transient disorder of attention, and cognition and its diagnosis was made by the patient’s medical team following the current recommendations and methods.[13,14]Bleeding events were defined as significant hemorrhages requiring surgery, hospitalization or antithrombotic therapy withdrawal. A baseline geriatric assessment was made during admission in all patients through interview with the patient, family or caregivers and referring to the patient’s status prior to admission. The complete in-hospital geriatric evaluation included the Barthel index(functional capacity), the Lawton-Brody Index (instrumental activities), the Pfeiffer test (cognitive status), the FRAIL scale (frailty), the Short Physical Performance Battery(SSPB) (frailty), the Charlson Comorbidity Index and the Nutritional Assessment-Short Form.[15-21]

2.3 Follow-up

Follow-up data was obtained by telephone contact at 6-month, and from the event reports by electronic records of each hospital. The occurrence of death, major bleeding or the need of new coronary interventions was registered. Additionally, a new geriatric evaluation was also determined by assessing the Barthel and Lawton indexes and the Pfeiffer test. Cognitive decline was defined as a loss of at least one point in the 6-month Pfeifer test. Functional decline was defined as a loss of at least ten points in the 6-month Barthel score or two points in the 6-month Lawton-Brody test.[22]

2.4 Statistical analyses

Categorical variables were described by frequencies and percentages, and statistical differences were analyzed using the χ2test or Fisher exact test when any expected cell frequency was < 5. The continuous variables were described either by the mean and standard deviation, or by the median and interquartile range. The statistical differences among the continuous variables were analyzed using student’s t test in case of a normal distribution, or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test in case of a non-normal distribution. Kaplan-Meier estimators of survival were built comparing patients who suffered delirium and those who did not. Finally, to evaluate the independent effect of delirium on 6-month mortality, a Cox regression model was implemented adjusting for propensity score weights (inverse probability of assignment weighting)including the potential confounding variables.[23]For ana-lyzing the association between delirium and the secondary end-point (6-month bleeding events), we used a logistic regression adjusted by the previously described method.Multiple imputation using chained equations method was applied when necessary (n = 5) applying the “mice” package in the R Project for Statistical Computing.[24]A P value< 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using STATA v.13 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) and R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing,version 3.3.2).

3 Results

3.1 Clinical characteristics

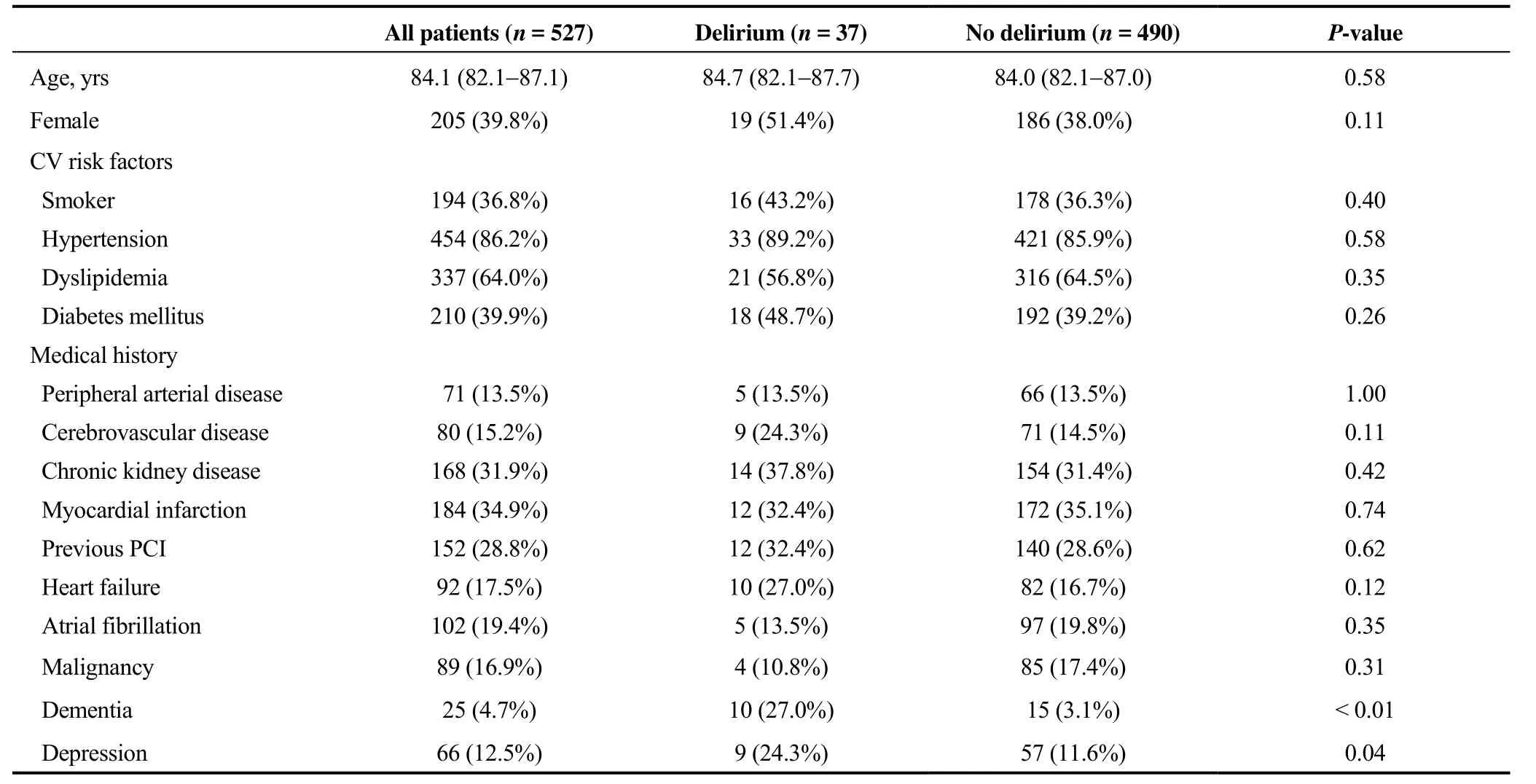

From 527 patients, 37 (7%) presented delirium during hospitalization. Table 1 summarizes the baseline clinical characteristics of the study population. Patients who developed delirium had more frequently a previous diagnosis of dementia or depression. We did not find statistically significant differences in any other main clinical characteristics between the two groups. Of note, there was a tendency towards a higher frequency of previous diagnosis of cerebrovascular disease and heart failure in those who presented delirium.

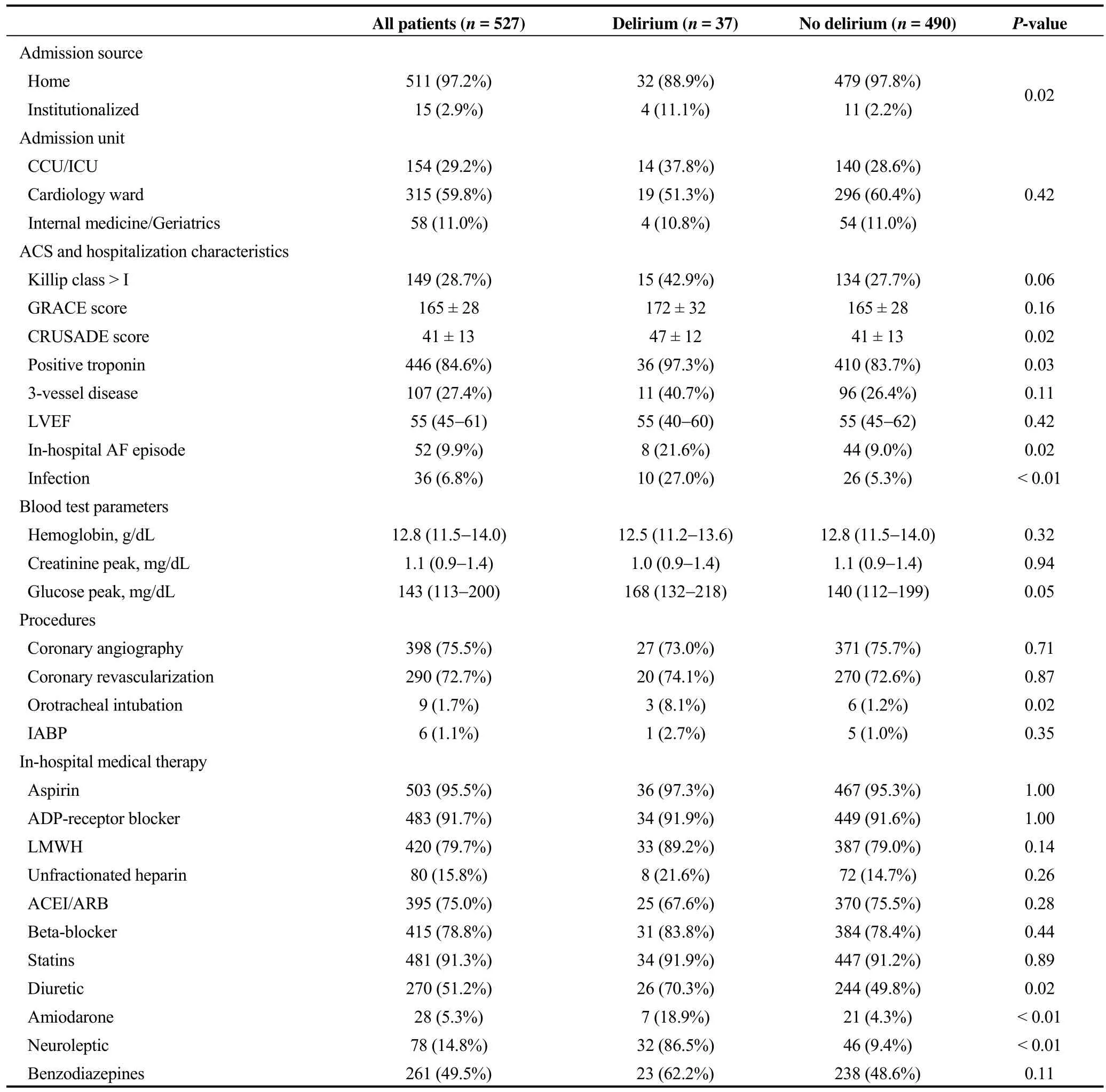

Table 2 shows the main features regarding the index hospitalization, the ACS characteristics and the procedures performed. Patients who presented delirium were more frequently referred from nursing homes. At admission, they had a higher Killip class, higher CRUSADE score punctuation; and presented more frequently elevated troponin levels. With respect to in-hospital complications, patients who developed delirium presented a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation, infections requiring antibiotic treatment;and they were more often treated with invasive mechanical ventilation, diuretic therapy, amiodarone, and benzodiazepines. On the other hand, both groups had similar rate of invasive treatment and coronary revascularization therapy during the admission.

3.2 Geriatric evaluation

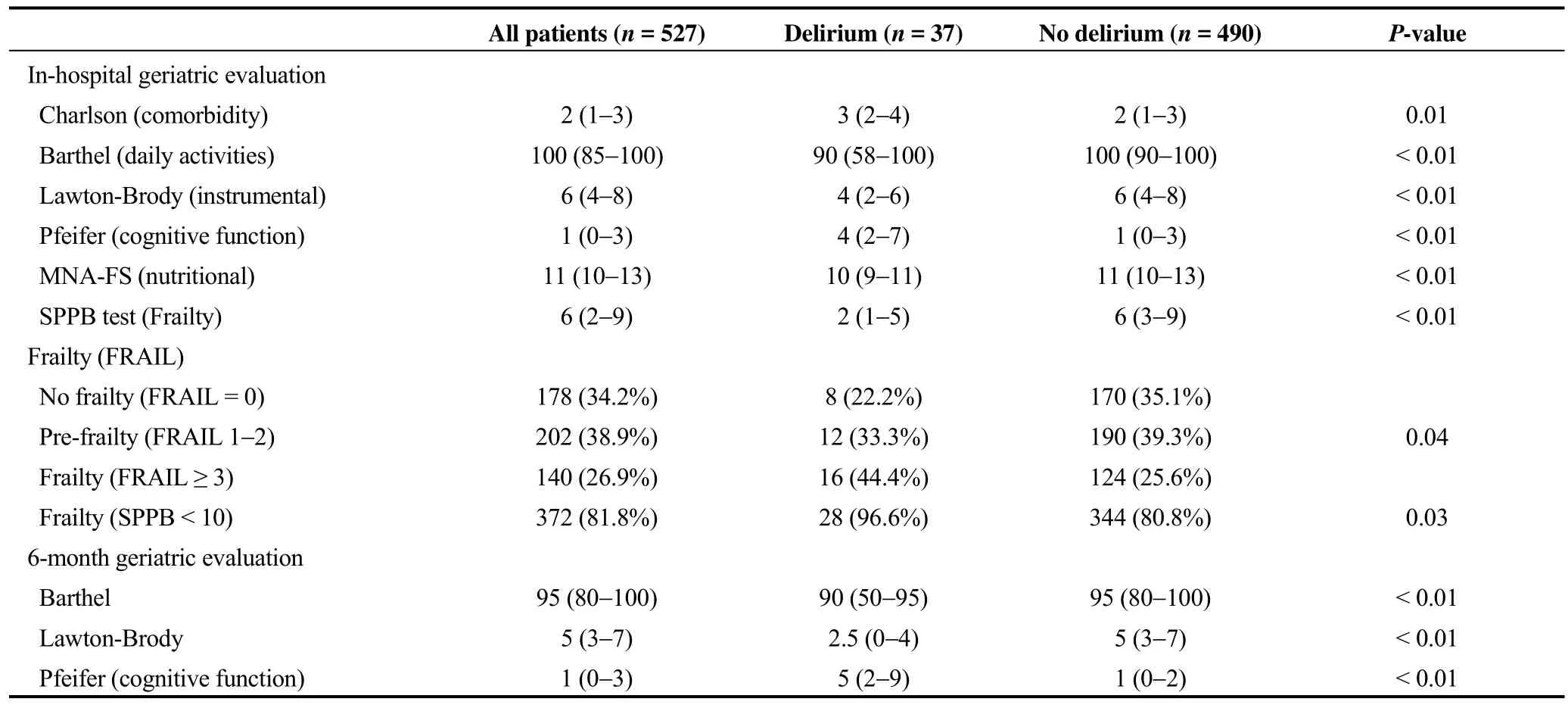

Table 3 summarizes the baseline and 6-month geriatric evaluation data. Patients who developed delirium were more comorbid, they had worse functional and instrumental capacities, and they also presented a poorer cognitive function and cognitive status. Remarkably, the prevalence of frailty(FRAIL score ≥ 3) in the entire cohort was 27%, and resulted higher in patients with delirium (44% vs. 26%, P =0.04).

3.3 Outcome

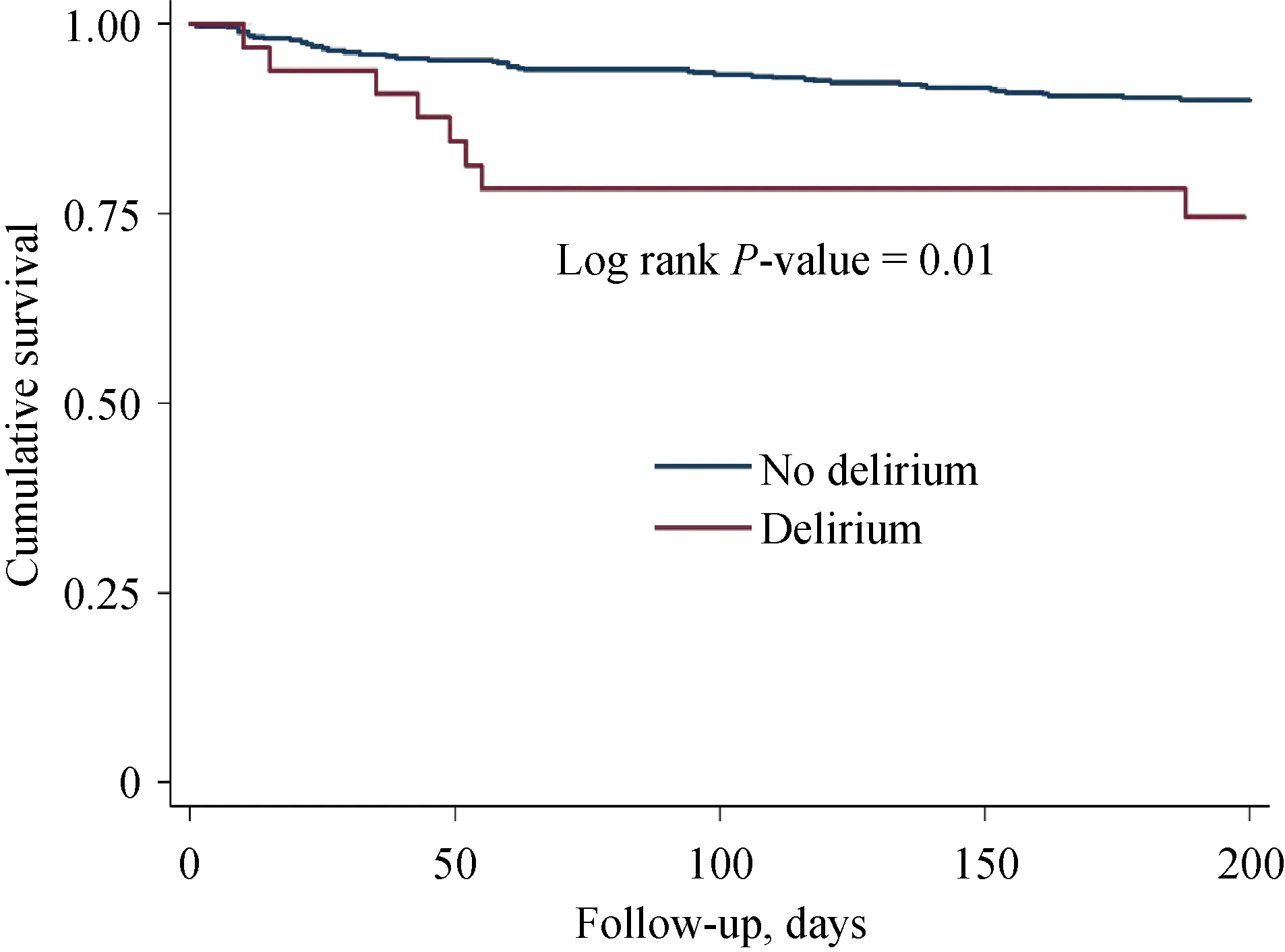

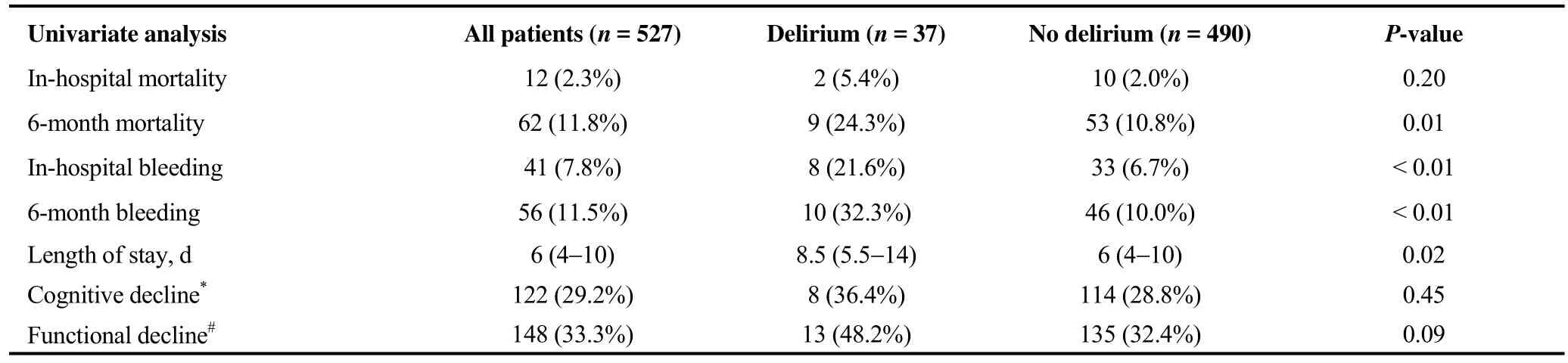

As shown in Figure 1, patients who developed delirium had higher non-adjusted overall 6-month mortality (24.3%vs. 10.8%, P = 0.01). Table 4 describes in-hospital and6-month outcomes. Patients with delirium had more frequent in-hospital and 6-month bleeding events and longer hospitalization. Our data did not reveal significant differences in the proportion of patients presenting 6-month functional decline or 6-month cognitive decline. After a Cox regression analysis with propensity score weighting including the following well balanced confounding factors: previous heart failure, depression, institutionalization, positive troponin, 3-vessel coronary artery disease, revascularization during admission, CRUSADE score, Killip class, atrial fibrillation episodes, need for mechanical ventilation, infection during hospitalization, diuretic treatment requirement, treatment with amiodarone, treatment with benzodiazepines and frailty; delirium persisted as an independent risk factorassociated with 6-month mortality (HR = 1.47; 95% CI:1.02-2.13, P = 0.04). Finally, a logistic regression analysis adjusted by the previously mentioned method showed that delirium was also independently associated with 6-monthbleeding events (OR = 2.87; 95% CI: 1.98-4.16, P < 0.01).

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population.

Table 2. Acute coronary syndrome characteristics, care and procedures.

Table 3. In-hospital and 6-month geriatric evaluation.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimators of survival comparing patients who presented delirium or not. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mortality data comparing those patients who developed delirium or not during the admission with a follow-up duration of 6 months (total n = 527), P-value is a log-rank test.

4 Discussion

4.1 Main findings

Our large multicenter prospective cohort provides reliable data about the frequency, clinical characteristics and prognostic implications of delirium in patients aged 80 or older admitted for NSTE-ACS. Our results show that up to 7% of octogenarians with NSTE-ACS develop delirium and that its appearance is a robust independent predictor of 6-month mortality. Additionally, delirium identified patients with higher risk of bleeding events and longer hospitalization.

Table 4. In-hospital and 6-month outcome.

4.2 Delirium incidence

The incidence of delirium in hospitalized patients depends on the setting of the study population. The highest rates have been described in postoperative populations(46%),[25]and in intensive-care unit ventilated patients(82%).[7]More specifically, an incidence of 20% has been reported in patients admitted to cardiac intensive care units,[26,27]and 17% in elderly patients admitted due to acute cardiac conditions.[28]In our study, the lower observed rate could be explained by the fact that the majority of our patients were admitted to the regular ward and they were overall in better clinical condition. For example, only 25%presented heart failure. Moreover, our study is based in a very recent cohort and it could be influenced by the growing interest and interventions designed for the prevention of specific geriatric complications.[29]

4.3 Predisposing and precipitant factors for delirium

The appearance of delirium depends on the coexistence of several predisposing characteristics and the presence of distinct insults that play the role of precipitating factors.[30]We identified depression, dementia or institutionalization as baseline characteristics that may help to recognize those patients more prone to present delirium. In addition, the geriatric tests show that the comorbidity, frailty and the diminution of the functional or cognitive capacities are variables closely related to its appearance. All these findings are consistent with the previously published evidence,[31-34]and it could potentially be used to screen and identify those elderly patients admitted with NSTE-ACS, these patients need more a proactive implementation of preventive strategies for delirium. Regarding the latter, our study shows some potentially preventable precipitants, such as infections or the use of diuretics. For instance, early removal of urinary or venous catheters, and minimizing the duration of mechanical ventilation could be useful to prevent delirium.[30]Additionally, excessive depletion of these patients leading to uremia or dyselectrolytemia are known to be related with delirium, and it should be reconsidered daily.[9]Finally, non-pharmacological multicomponent approaches for prevention of delirium are effective strategies likely applicable to this specific population.[35,36]

4.4 Delirium and outcomes

Delirium has been related to higher mortality in different medical and surgical populations,[37,38]and it has also been evaluated in patients with acute cardiac conditions. Uthamalingam, et al.[39]observed that delirium was independently associated with higher in-hospital and 90-day mortality in patients admitted with acute heart failure in a single center retrospective cohort study. In accordance with the above,Noriega, et al.[28]found that delirium was associated with higher adjusted 12-month mortality in old patients admitted for acute cardiac conditions; however, only a third of them were admitted due to ACS and all patients were included in the cardiology department of a single university hospital.Finally, in critical cardiac care settings, Pauley, et al.[26]and Sato, et al.[27]reported that delirium was independently associated with in-hospital and 60-day mortality, respectively.To our knowledge, this is the first study addressing the short and long-term prognostic implications of delirium in elderly patients admitted for NSTE-ACS in a large multicenter and non-selected population. We found that delirium is a robust independent predictor of 6-month mortality and thus, this information could be useful for risk stratification in this growing and complex population. Moreover, delirium also seems to be associated with a higher risk of bleeding and longer hospitalization.

Validated risk scores are useful tools to predict outcomes in ACS,[10,11]and their use has been generalized in the last decade.[40]However, elderly NSTE-ACS patients have specific geriatric syndromes; such as frailty or delirium that may influence the prognosis,[41]and they are not considered in risk-stratification tools. In a recent cohort study in old patients admitted for ACS, frailty and comorbidity were identified as mortality predictors, and they were found to significantly reclassify risk beyond age.[42]Nonetheless, the specific impact of delirium was not studied and its potential predictive utility has not been tested. Based on our data, the appearance of delirium is related to a poorer prognosis and it should be useful when estimating the risk of death in these patients. Besides, since it is a potentially preventable and treatable cause, further research in this field would be of special interest.

Finally, our findings show a high proportion of patients presenting 6-month cognitive and functional decline, but it did not result to be significantly associated with delirium.Delirium has a transient nature,[13]and these patients have a correct recovery after the index hospitalization. Therefore,the cognitive or functional decline observed may be associated to other important factors, such as age or previous cognitive impairment.[43]

4.5 Study limitations

Our study has some limitations. This is a post-hoc analysis, and it could be influenced by the usual biases of these types of studies. Additionally, given the descriptive nature of the study, there might be residual confusion affecting the association between delirium and mortality despite the adjustment by the propensity score. Moreover, some signifi-cant clinical variables as the presence of other geriatric syndromes, such as immobility or urinary incontinence, and data about the use of physical restraints or central vein or urinary catheters are lacking. Finally, delirium was not screened daily; thus, it possibly lead to underdetection of hypoactive delirium.

In conclusion, our study provides the first description regarding the unfavorable effect of delirium on the prognosis of elderly patients with NSTE-ACS. Our data, based on a broad and systematic geriatric assessment both on admission and 6 months after discharge, are of clinical interest and it may potentially pave the way to the addition of specific geriatric syndromes to currently existing risk scores in this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andreu Ferrero-Gregori for assistance with statistical analysis. This study was supported by the funding from the Spanish Society of Cardiology. There is no conflict of interests to be declared.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2019年2期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2019年2期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Removal of refractory thrombus by 5F child catheter in patients with subacute myocardial infarction

- A rare case of primary well-differentiated angiosarcoma of the right atrium

- Impact of main vessel calcification on procedural and clinical outcomes of bifurcation lesion undergoing provisional single-stenting intervention:a multicenter, prospective, observational study

- Bleeding risk assessment in elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome

- Frailty and acute coronary syndrome: does gender matter?

- Frailty in patients admitted to hospital for acute coronary syndrome: when,how and why?