GRIM FAIRY TALES

BY DAVID DAWSON

GRIM FAIRY TALES

BY DAVID DAWSON

A passport to the netherworld, effectively a letter to the bureaucratic ruler of hell. Collected in Henry Doré’s 1914 reprint of Researches into Chinese Superstitions.

Vampires, ghosts, and were-beasts: How foreign demonologists catalogued China’s homegrown horrors

外國(guó)傳教士眼中的中國(guó)神怪大觀和民間信仰

The tale, over a century old, starts simply: A researcher asks a former governor why he keeps moving his arms, as if swinging bells.

The answer: vampires.

Dutch demonologist Jan Jakob Maria de Groot was researching China’s supernatural history in 1907 when he interviewed “Tsiang,” who claimed to be a governor of a town in Pehchihli (most likely modern-day Hebei) that was under siege from a kiang shi, or Chinese vampire—jiangshi (僵尸, “stiff corpse”) in modern Romanization.

These “l(fā)iving corpses” de Groot explains, “break forth from their tombs and satiate their cravings for human blood.”

Pehchihli was apparently under siege from a creature“soaring through the air, to devour the infants of the people.” Despite people locking their doors at nightfall, children were going missing. The town pooled money for a Daoist magician, who set up his altar on an auspicious day.Tsiang demanded to know how, precisely, he planned to stop this marauding vampire.

“Corpse specters generally fear very much the sound of jingles and hand-gongs,” the magician told him. “When the night comes, you must watch the moment when the spectre flies out, and forthwith enter the grave with two big bells.” But there were risks: “Do not stop ringing them, for a short pause will give suffice for the corpse to enter the grave, and you will then be the sufferer.”

At midday, a crowd gathered and trapped thekiangshiin their midst. As the magician performed his rites, the governor doggedly pursued the vampire, ringing his bell until the crowd had burned the stiff corpse. “Both my arms then remained in constant motion, and they have been diseased like this to this day,” he explained to de Groot.

Echoes of legends of the Eastern European vampire did not escape the Dutch researcher (Bram Stoker’s seminalDraculahad been published just a decade before). De Groot mused on the similarities, including the fact that both varieties are vulnerable to fire.

The Dutchman was one of several foreign researchers looking into China’s menagerie of myth and lore. Throughout the late 19th century, he traveled through China collecting information, basing himself in presentday Xiamen, Fujian province, with a few tours to other regions. A few years later, Henry Doré, a French researcher, would build upon de Groot’s work in his writings on Chinese witchcraft and charms, including details on summoning spirits and Chinese concepts of Hell.

De Groot’s research became a series of books,The Religion of the Chinese, detailing the evolution of Chinese spiritual practices from the various forms of animism through to organized religious rites, be they uplifting or macabre. Many of his findings were from historical texts; others were based on conversations with Chinese about their beliefs and superstitions. It was from the latter exchanges that many of his best creepy-crawly stories emerge, fodder for Grimm-style fairy tales, albeit with Chinese characteristics and not intended for children.

The vast majority of supernatural creatures were shapeshifting demons; one of de Groot’s works has separate chapters dedicated to water, earth, and plant demons, and different types of animal demons such as tiger, dog, insect, and even bird demons. In many cases, these shape-shifters are omens, taking bestial form right before a gruesome death takes place.

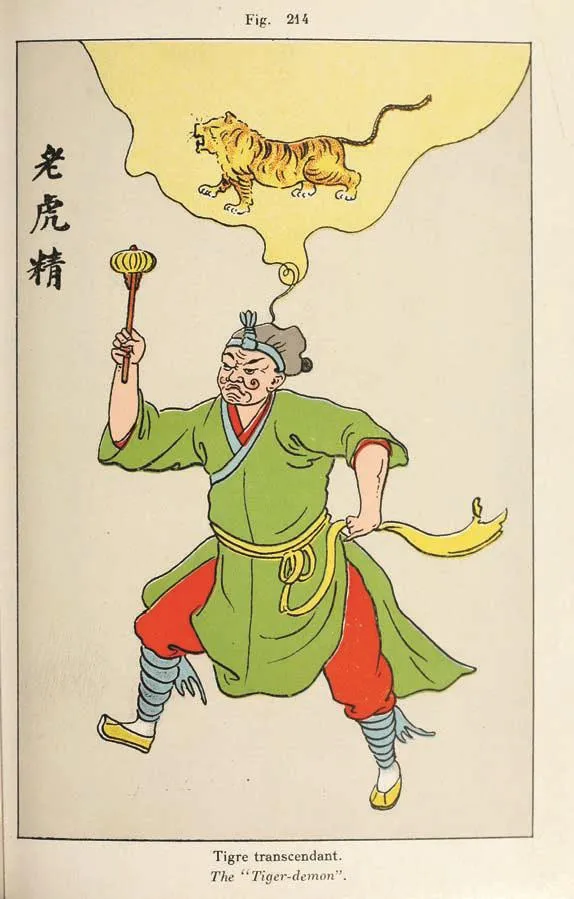

Much as wolves and their lycanthrope counterpart stalked the forest, mountains, and villages of European imaginations, Chinese were-beasts took their most fearsome form in the native tiger. The similarities, de Groot notes, are striking: “A wound inflicted on a were-beast is believed in China to be visible also on the corresponding part of its body when it has re-assumed the human shape. This is also a trait of our own lycanthropy,” he writes of “tigerdemons,” referred to here aschu tu-shi.

A typical tale begins with a man out chopping firewood late at night, under a waxen moon. “Overtaken by the dark, he was pursued by two tigers,” de Groot recounts. “As quickly as he could, he climbed a tree, which was, however, not very high, so that the tigers sprang up against it, but without reaching him.

“THE CHU TU-SHI SUDDENLY ROSE FROM HIS BED, RAN ABOUT, CHANGED INTO A TIGER, AND CHARGING UPON THE MEN ESCAPED”

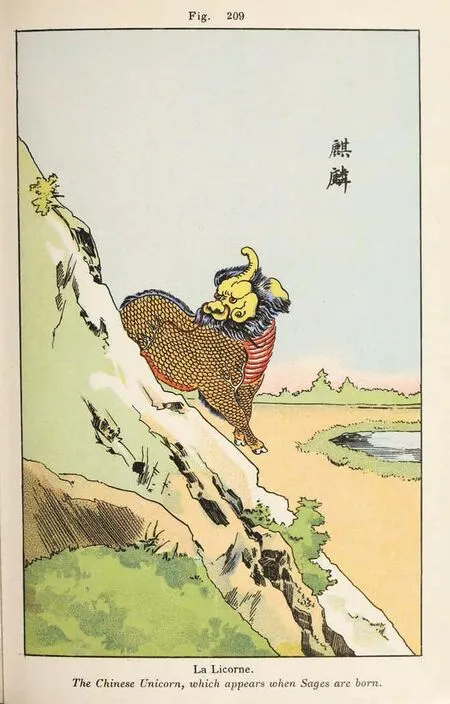

A “Chinese unicorn,” or qilin, said to appear when sages are born

One tiger went to fetch another, “l(fā)eaner and longer, and consequently peculiarly fitted to catch prey.” The protagonist, seemingly doomed, strikes back: “The moon was shining brightly that night…just when the brute grabbed at him again, he dealt it a blow and hacked off its fore-claw. With loud roars the tigers ran off one after the other, and not until the morning the man went home.”Later, the woodchopper related his tale to a group of villagers, who managed to track down a local who had“wounded his hand” and was “in bed.” The prefect of the district ordered his underlings to arm themselves with swords, besieged the dwelling, and set fire to it: “Thechu tu-shisuddenly rose from his bed, ran about, changed into a tiger, and charging upon the men escaped; and it is unknown whither he went.”

The horned yellow dragon was among the most revered mythical creatures

A depiction of a were-tiger, or chu tu-shi

Tiger-demons could also assume female forms, which were apparently far deadlier then the male, de Groot writes:“The most horrid specimens of the tiger-demon class, which Chinese fancy has created, are those who assume a woman’s shape with malicious intent, and then tempting men to marry them, devour them in the end, and all the children in the meantime produced.”

These animal demons are a recurring theme throughout Chinese literature, particularly snakes. One of China’s most beloved fairy tales is the Legend of the White Snake, first recorded in Feng Menglong’s collectionStories to Caution the World(《警世通言》) in 1624, about a female snake spirit who lurks in Hangzhou’s West lake. Yet the serpent’s role in Chinese mythology is not as malevolent as it is in a lot of Western literature. As de Groot notes, “according to at least as many stories, apparitions of vipers and serpents have proved to be propitious.”

Indeed, encountering a supernatural creature can have positive effects. Take the “Black Calamities” (黑眚h8ish0ng) that struck China in 1119, 1126 and, “most calamitously,”in 1476. These were natural catastrophes, caused by specters acting as “retributive agents from Heaven,” and sometimes taking the form of an animal such as a tortoise or donkey shrouded in black mist. The most calamitous types were described as resembling “black vapors” or“rains of sand, ink or black peas,” and were often seen as harbingers of doom brought on by a ruling dynasty that was not fulfilling the Mandate of Heaven (indeed, quoting from the officialHistory of the Ming Dynasty, de Groot details the efforts of one Ming emperor to forestall disaster, appearing at an altar within the Forbidden City to offer prayers, confess his sins, and send out envoys “to examine the cases of prisoners throughout the empire”).

Ominous as they sound, the end results of the Calamities weren’t necessarily bad. Take the disaster of 1476: Black Calamities had been striking by night, wounding guards in“the western city.” The emperor, fearing panic, issued a gag order—the supernatural incidents were effectively classified top secret, and guards were tasked with catching them.

His secretary of state had a different solution, and issued an eight-point decree. The power of the Dalai Lama was curbed and frontier armies boosted, while the king, too, was subject to new measures. “Except the customary tribute from the four quarters of the world, no valuables should be accepted by the Throne,” the decree, as communicated by de Groot, reads. “People of every class and rank should be allowed to report the truth personally to the authorities.”Envoys were once again sent to examine prisoners, “inorder that justice might be done to the wronged and oppressed.”

The decree’s security measures were effective in fighting corruption—which was likely their purpose. Fear of ghosts, de Groot points out, “may in China impose upon emperors the introduction of important political measures and improvements of the system of government.”

Where de Groot researched creatures that went bump in the night, Doré focused primarily on superstitions regarding the dead. Much of this focused on Hell, or the Chinese concept of it—summoning spirits, ensuring their safe passage to the netherworld, and even “informing the ruler of Hades of the exemplary life of the deceased.” It’s important to note here that this was the Buddhist King of Hell, who was no Satan. Rather than a Faustian pact, the summoning might be better viewed as petitioning a heavenly bureaucrat for a favor, in return for worship.

The benignseeming Chinese King of Hell, seen here presiding over numerous grisly punishments

But if its ruler appears innocuous, Hell itself is just as horrifying (and specific) as the Christian version. Doré recounts a dozen different courts, each with a multitude of dungeons to punish sins as diverse as murder and opening someone’s mail: One court doles the punishment of making sinners stumble down a street strewn with oily beans, another has sinners’ eyes gouged out.

The first volume of Doré’s multi-volumeResearches into Chinese Superstitions(which reference de Groot extensively), published in 1911, lists charms that can rescue people’s souls from the many misfortunes that may befall them in the afterlife. There was a school of belief that stated each man has two souls—one born of the earth, and one that comes from the cosmos. The earthly soul, known askwei, returns to the earth or becomes a ghost, while the latter passes on to the netherworld (Confucianists of the time argued it just disappeared at death) where it may encounter all manner of strife.

One could make appeals on behalf of a relative’sshenby buying charms, or “petition talismans,” a racket similar to the Catholic selling of indulgences. Almost any untimely or distressing death could allow theshento succumb to evil spirits: People who committed suicide or were assassinated; victims of unjust lawsuits; people who died in prison, were drowned, or poisoned by a doctor’s prescription—every unfortunate circumstance had its own unique charms to ensure better treatment in the afterlife, and ensure the infernal bureaucracy wouldn’t make any mistakes.

Women who died in childbirth were sometimes trapped in a horrific hell known as the “bloody pond” from which only a ceremony by witches could release them; there were also petitions for “wandering and vagabond souls” that might have risked falling prey to malevolent demons. Aside from bureaucratic bungling and lost souls, the netherworld was just as prone to earthly problems like corruption and theft: One could burn and send a “paper safe” for dead relatives to store their valuables.

And this intangible spiritual material was most definitely valuable in cold, hard, earthly cash. In cases where an inheritance was disputed, a claimant might literally bring the soul of their relative in an envelope to prove they were the rightful heir to the family fortune; the monks, also, were making fortunes through selling such charms.

Some of these superstitions survive, albeit in token form. On Tomb-Sweeping Day, many Chinese practice a range of regional customs to honor their ancestors, and it’s not uncommon to see small fires on the city streets at night, as the bereaved burn paper charms for the deceased. Instead of just money, though, today’s mourners are just as likely to burn a paper iPhone or Audi. It seems even the netherworld keeps up with the latest trends.